By Noortje Jacobs and Steven van der Laan

Do animals carry legal obligations? To the twenty-first century reader of Shells & Pebbles this question might appear to be odd. Surely, only in fables pigs are summoned to appear before a judge to be held accountable for any misdemeanour. Not quite. In past centuries, animal trials were not unheard of. In fact, one might wonder with the advent of the animal rights movement in the twentieth century, whatever happened to animal duties? A blog post on a cat in court.

When considering the origin of the international animal rights movement, historians often point to the publication of Animal Liberation in 1975 by the moral philosopher Peter Singer.[1] Although concern for animal suffering is certainly not an exclusive twentieth century phenomenon (the English Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, for example, was founded in 1824), it was only in the final quarter of the twentieth century that the juridical lingo of ‘animal rights’ gained widespread popularity. Similarly, it was only after the 1980s that the subject of animal law came to be widely taught in universities all over the world.

According to its critics, the idea that liberty rights can be extended to animals is absurd. The conservative philosopher Roger Scruton, for example, argues that animals are incapable of entering into a social contract and therefore cannot lay claim to legal protection: “To use these strategies on animals is to misuse them; for if animals have rights, then they have duties too. Some of them – foxes, wolves, cats, and killer whales – would be inveterate murderers and should be permanently locked up. Almost all would be habitual law-breakers”.[2]

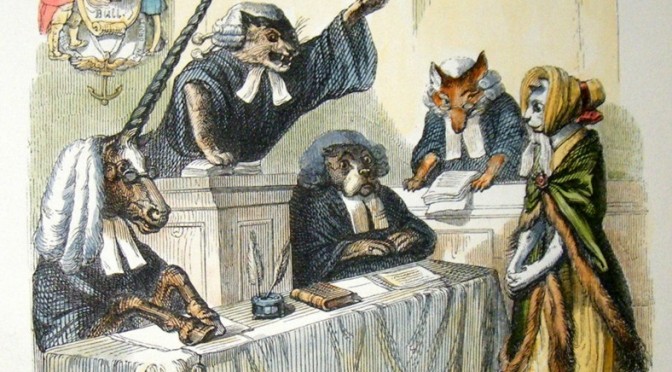

Convicting wolves as vicious murderers, snakes as cunning deceivers and rats as low-life thugs does perhaps sound absurd from our contemporary perspective. In past centuries, however, it was by no means uncommon to think of animals as habitual law-breakers and try them as such in human courts. In 1906, for example, more than one hundred accounts of animal trials were collected by historian Edward Evans in his book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals.[3] As many past accounts of similar trials must not have survived the ages, Evans’ collection probably only presents the tip of a much larger iceberg.[4] Oft-cited examples include the conviction of a killer pig in 1386, the 1522 trial of a gang of thieving rats and the 1750 acquittal of a well-behaved she-ass which could not be held accountable for the bestialities of her male owner.[5]

A more recent example of animal prosecution may be found in the Dutch agricultural magazine De Veldbode of 1928. Tucked away between an article on Belgian egg consumption and the weekly horticulture announcements, De Veldbode makes mention of an English court case concerning the prosecution of a cat.[6] The furry animal stood trial for having allegedly slain eight pigeons and two bantams. One salient detail: the cat itself was in no state to attend the hearings, for its owner had taken matters into his own hand after discovering ‘his precious with a pigeon in its mouth’. The cat, in fact, was dead.

Judging from the article, a legal conviction of a deceased animal was regarded to be simultaneously necessary and problematic in early twentieth-century England. Necessary, because the owner of the pigeons and bantams desired financial compensation for his loss. Problematic, because convicting a cat, also when it was dead, could have serious consequences for the constitutional status of the entire species. The court case therefore amounted in two consecutive appeals in order to determine a final ruling. According to the article in De Veldbode, witnesses testified in court that the cat in question had been ‘of good character’.[7] Was it reasonable, therefore, to hold this particularly well-behaved creature accountable for securing its daily bread? It took two consecutive appeals to determine the final verdict. In the end, it was only the House of Lords which determined that the ‘freedom of the species’ outweighed the financial losses of the accusing party.

From a present-day perspective, animal trials have a somewhat alien ring to them. As animals cannot consent to intercourse, laying with them amounts to rape. Hence, the only animal standing trial in such cases is the human pervert. A hoard of rats might be a gang, but to consider them thieves would attribute anthropomorphic qualities to them, which they cannot possible have. Purposefully trespassing upon property rights is a felony only human beings can commit. Cats, of course, are neither of good nor bad character. They are simply programmed by nature to purr, hunt and sleep and that is all they do. If anyone is to be held accountable, it is the cat’s human owner, who should have kept his pet indoors and fed it more Whiskas.

But animal trials in past centuries did not just take place to convict animals for all they did wrong. On the contrary, as the case of the cat in court shows, also animals had constitutional rights which were worth defending in court. Similarly, past cases show that animals were also believed to have property rights or were at least entitled to similar claims on God’s earth as humans. In the sixteenth century, for example, when a plague of weevils ravaged the fields of France, the townspeople of Saint Julien decided to set aside a piece of land for the insects to ‘obtain their needed sustenance without devouring and destroying the town’s precious vineyards’.[8] The insects’ (human) attorney, who received his pay from the public of Saint Julien, even objected that his clients could not accept this offer, because the land was ‘sterile and not suitable to support the needs of the weevils’.[9] Humans had entitlements, but animals too. And differences between species were not so stark to assign agency and reason to one single species, while denying it to all others.

Curiously, it thus seems as if concomitant to the rise of the animal rights discourse in the twentieth century, the decline of a long-perceived animal agency has set in. An animal in our contemporary society cannot possibly commit a crime. It can only fail to behave in a way that we, humans, expect it should have behaved. When this happens – when a dog is perceived as vicious, a bull as aggressive or an elephant as mad – a human expert is called to decide the animal has to be “put down”. The ‘freedom of the species’ or a ‘right to self-defence’ does not play a role. Comparing such procedures with medieval animal trials, therefore, one may wonder what we mean nowadays when we call for animal liberation or a more humane treatment of non-human creatures.

[1] Peter Singer, Animal Liberation, (1975: Harper Collins).

[2] Roger Scruton, ‘Animal Right’s, City Journal, 2000, retrieved from http://www.city-journal.org/html/10_3_urbanities-animal.html (23-02-2014).

[3] Edward Evans, The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, W. Heinenman, 1906.

[4] Jen Girgen, ‘The Historical and Contemporary Prosecution and Punishment of Animals’, Animal Law, 2003, vol. 9, p.106.

[5] Animal trials such as these provide good blogging material and we are certainly not the first to use the topic as such. Especially worth reading is the post of Nicholas Humphrey, Bugs and Beasts before the law, on The Public Domain Review: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/03/27/bugs-and-beasts-before-the-law/.

[6] Poes voor de rechtbank, De Veldbode, no.1323, 26 mei 1928.

[7] Ibid

[8] Girgen, p. 104.

[9] Ibid, p. 104.