By Daniel Stinsky

Maps contain lots of information in a condensed and abstract visual format. We trust maps to depict reality, and we trust that they are produced with scientific rigor. But as the fairly recent case of a “phantom island” in the Coral Sea shows, maps can contain false information, even in the age of satellite imagery. A historical perspective on the way geographical data was communicated in the past helps to understand how such false information got reproduced and eventually found its way from the late 18th century into Google Maps.

The island that never was

In November 2012, a team of Australian geoscientists sailing the Coral Sea west of New Caledonia were puzzled by conflicting data. The maps they had onboard their research vessel showed an uninhabited island about 1½ times the size of Manhattan in close proximity. It was labeled “Sandy Island”. Yet, their instruments indicated that the ocean in this area was 1,400 meters deep. How could an island be anywhere close if the water was so deep?

“It’s on Google Earth and other maps so we went to check and there was no island. We’re really puzzled. It’s quite bizarre”, one of the geoscientists said in an interview with BBC News. Had Sandy Island sunken into the ocean like the legendary Atlantis? Was it destroyed by climate change or the devastating tsunami of 2004? The geoscientists found no evidence for that. In the end, it was concluded that there is no Sandy Island, and that there never was. Publishers like National Geographic declared that they would erase the phantom island from all their map products.

The strange case of Sandy Island shows that the Age of Un-discovery might not be over yet. False geographical information can sometimes be reproduced for centuries and may appear in our most popular and most trusted sources, including Google Maps. The Australian geoscientists found that Sandy Island was recorded in scientific publications since at least the year 2000. In fact, it had been around for much longer. The blog Maps of Sandy Island shows the strange island on a map already in 1774.

But how did it get there? And why was the mistake reproduced for such a long time? This blog post does not solve the riddle of the Phantom Island, but it suggests that a historical perspective on the way geographical information was produced, communicated and reproduced in the past can help to understand what might have happened here.

The mystery of the Niger River

The Niger is a river in West Africa. It is half the world away from Sandy Island and the Coral Sea, but serves well as a case to exemplify how geographical information was produced and communicated in the past. Little more than its name was known to European scholars before the late 18th century. It was known from ancient and Arabic sources that a river called Niger flew close to Timbuktu, then a city inaccessible to Westerners that many imagined as an African El Dorado, plastered with gold earned in centuries of cross-Saharan trade.

But Europeans did not know where the river’s sources were, in which direction it went, or where it flew into the sea. Ancient sources suggested that the Niger might flow from west to east into a gigantic lake in the midst of central Africa, or that there might even be a connection with the Nile. The 16th century account of the Moorish traveler Leo Africanus claimed it flew in the opposite direction, stemming from the inland lake and opening into the Atlantic.

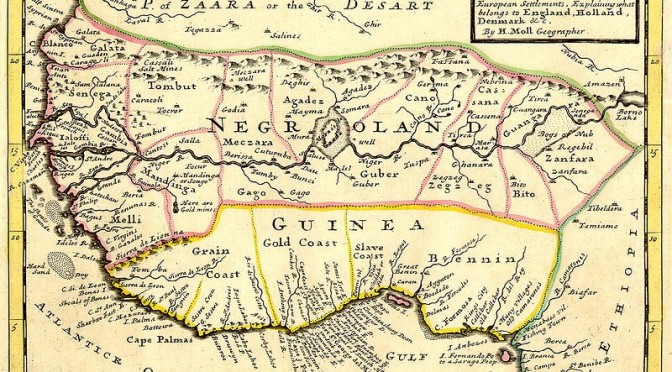

An English map dated 1729 shows the West African coast line and European trading posts and settlements along it.[1] The Niger is depicted in the center, flowing from east to west and opening into the Atlantic, approximately at the mouth of the river we now call Senegal.

The map differs dramatically from early modern maps containing decorative elements like sea monsters and little images of ships and fortified cities. It is interesting to note the pragmatic way in which Europeans named coast sections according to the resources they could retrieve from there – Grain Coast, Gold Coast, Slave Coast. Colors were used to indicate political spheres of influence. A scale was added to determine altitude and longitude. Altogether, the map looks very modern – and thus more trustworthy to modern eyes than many of its contemporaries.

But on closer inspection, we get the impression that the cartographer was afraid of admitting too many white spaces. Rivers and mountains are added in the Zaara (Sahara) desert. Colored lines, the tropic of cancer and the box in the upper right corner are all conveniently placed to cover the white. The entire center of the map relies on little more than speculation based on Leo Africanus. The map, with its modern, sciency appearance thus transformed geographical information from the vague narration of a 16th century traveler into a seemingly trustworthy depiction of reality.

The African Association and Mungo Park

Though little was known about the Niger in the 18th century, the mysterious river sparked the imagination of some wealthy gentlemen in London. In 1788, a club called the African Association was formed. Its purpose was, according to its self-description, “to promote the cause of science and humanity, to explore the mysterious geography, to ascertain the resources, and to improve the condition of that ill-fated continent.”[2] The club included people who shared an interest in Africa, albeit for very different reasons. It was led by the prominent explorer and botanist Joseph Banks, and William Wilberforce, leader of the abolitionist movement, was a founding member. But merchants and entrepreneurs with a strong commercial interest joined the African Association as well. Geographical information about the unknown interior of West Africa was crucial to all their interests. By gathering this information and creating reliable map material, they hoped to convince the crown to pursue a permanent British presence in the region.

The mysterious Niger River was crucial to the cause of the African Association. A navigable waterway would provide access to the continent’s interior and allow for exploration as well as commercial penetration. The strategy of this gentlemen’s club was to finance individual explorers for one-man-expeditions, who, in case they survived their journey, should then help to convince HMG to fit out a bigger expedition. Yet, to embark on a journey to West Africa was dangerous at the time and entering the swamps and jungles beyond the coastal line almost suicidal. The reason was malaria. The disease was deadly, especially to European crews unaccustomed to it, which suffered a very high mortality rate. A sea shanty warned: Beware beware, the Bight of Benin: one comes out, where fifty went in![3]

It was thus not easy to find volunteers to undertake the expeditions the African Association called for. Their first successful explorer was Mungo Park, a Scottish doctor and botanist. One of the most crucial objectives for Park’s mission was to determine the Niger’s flow direction. Park returned to Britain in 1797, after being lost for two years in West Africa. His return was sensational, and his book Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa became a bestselling tale of adventure and inspiration to the following generations of explorers. Mungo Park also became the inspiration for a 19th century literary archetype, the white explorer-hero driven into hostile, faraway lands by scientific curiosity. Park survived fever, captivity and the complete loss of his equipment. To stay alive, he relied heavily on the help of natives, who also guided him to the Niger River:

[…] as I was anxiously looking around for the river, one of them called out geo affili, (see the water); and looking forwards, I saw with infinite pleasure the great object of my mission; the long sought for, majestic Niger, glittering in the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at Westminster, and flowing slowly to the eastward.[4]

Mountains of Kong

Park had thus proven that the account of Leo Africanus regarding the Niger was wrong: the river actually flew in the exact opposite direction. But the discovery also opened new questions: what caused the river to flow eastward, and not westward into the sea? James Rennell, a cartographer in service of the African Association, believed that the answer was to be found in excerpts of Park’s own travel journal:

I gained the summit of a hill, from whence I had an extensive view of the country. Towards the southeast, appeared some very distant mountains, which I had formerly seen from an eminence near Marraboo, where the people informed me, that these mountains were situated in a large and powerful kingdom called Kong […].

Rennell speculated that these mountains caused the unusual course of the river. He drew two maps, which were included in the first edition of Park’s Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa.[5] Although they were mentioned only briefly by Park, the “Mountains of Kong”[6] appeared as a seriously impressive mountain range in Rennell’s maps, covering a length of several hundred kilometers:

The mountains of Kong, as you might have guessed, do not exist. But they proved to be a very persistent myth. The mountains of Kong appeared on all major commercial maps of the 19th century.[7] Even as the 19th century was drawing to an end, more than 80 years after the first publication of Mungo Park’s Travels, geographers were looking for them. The African Association had now become the Royal Geographical Society and an article published in their journal in 1882 insisted that a mountain range in the area must exist, even though no evidence had ever been found.[8] It was only when the French explorer Louis Gustave Binger established that the mountains were fictitious in his 1887-1889 expedition to chart the Niger River that most cartographers stopped including the mountains of Kong.

Why was this myth so persistent? From Rennell’s perspective, the existence of the mountain range made a lot of sense. It helped to explain several things that Park had observed, including the course of the Niger River, but also rainfall patterns in the area. It certainly helped that Rennell’s maps were usually published together with Mungo Park’s bestseller. This way, the information did not only spread rapidly, but was also continuously reprinted throughout the entire 19th century. Through Rennell’s maps, the mountains of Kong found their way into other publications, such as atlases and encyclopedias. They were last found in an Austrian middle school atlas printed as late as 1905.[9]

Narrating space

Considering that it took a hundred years to rid cartography of a gigantic mountain range that never existed, the discovery of a phantom island in the Coral Sea somewhat dwarfs in perspective. But a pattern emerges for the construction of knowledge about space: narrative accounts of discovery and exploration like the ones by Leo Africanus and Mungo Park lost their ambiguity and became perceived as reliable information once they were translated into maps. 19th century maps of areas rarely traveled by Europeans may be described as the visual summaries of travel journals; maps are narrations about space. But without added context, maps do not reference whether information is doubtful – sheer speculation thereby transformed into reliable and unquestioned knowledge. This does not necessarily explain the circumstances of how the fictitious Sandy Island was first created, but it does help to understand how this tiny bit of false geographical information was carried on for more than 200 years, from the late 18th century all the way to 2012.

o-o-o

Daniel Stinsky is a PhD candidate at Maastricht University. His research is about the history of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

[1]’Negroland and Guinea with the European Settlements, Explaining what belongs to England, Holland, Denmark, etc’. By H. Moll Geographer (Printed and sold by T. Bowles next ye Chapter House in St. Pauls Church yard, & I. Bowles at ye Black Horse in Cornhill, 1729, orig. published in 1727), via: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Negroland_and_Guinea_with_the_European_Settlements,_1736.jpg

[2] Sinclair, William: The African Association of 1788, in: Journal of the Royal African Society, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Oct., 1901), S. 146.

[3]Temperley, Howard: White Dreams, Black Africa. The Antislavery Expedition to the River Niger 1841-1842, London 1991

[4]Park, Mungo: Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa (1799), Durham / London 2000, p. 194. Original emphasis.

[5] Rennell, James: Geographical Illustrations of Mr. Park’s Journey, in: Park, Mungo / Ferguson Masters, Kate (ed.): Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa (1799), Durham / London 2000.

[6] Ibid, p. 224.

[7]Basset, Thomas J. / Porter, Phillip W.: ‘From the Best Authorities’: The Mountains of Kong in the Cartography of West Africa, in: The Journal of African History, Vol. 32, No. 3 (1991).

[8]Burton, H.F.: The Kong Mountains, in: Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, New Monthly Series, Vol. 4, No. 8 (Aug., 1882), S. 484-486.

[9]Basset, Thomas J. / Porter, Phillip W.: ‘From the Best Authorities’: The Mountains of Kong in the Cartography of West Africa, in: The Journal of African History, Vol. 32, No. 3 (1991).