By Constance Sommerey

“Guard your children!”[1] was a demand that echoed through multiple Prussian newspapers in 1877 (Depdolla 1939). It was uttered by a very concerned protestant minister who warned parents against the moral state of emergency at Prussian schools. The root of all evil? The incorporation of Ernst Haeckel’s evolutionism into biology classes. Five years later, the Prussian ministry of education banned biology as a whole from the final years of secondary education. No pupil was to learn about evolution in the institutional setting of the classroom.

This blog post has two functions. I will tell you the story of Haeckel’s far-reaching impact on German biology education during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. It is a story that illustrates how our understanding of science is shaped by the ethical and political outlook of society. With this intriguing story I hope to whet your appetite for the topic of ‘Illegal Science’.

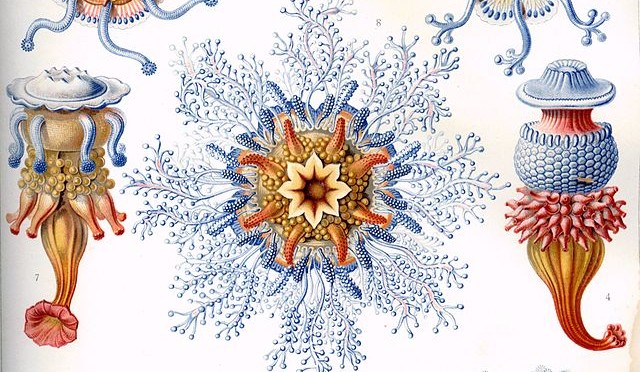

In the fall of this year, mediamatic will organize an exhibition on Haeckel’s beautiful art published in Kunstformen der Natur (1899). You are already familiar, albeit unknowingly, with his work. Scroll upwards – the shells depicted on the top of this page were published in Haeckel’s Kunstformen. Here are some more examples of sea animals from this stunning collection:

It is not only Haeckel’s art that is fascinating, however. Next to the exhibition, we want to take the case of Haeckel and German biology education as a starting point for a conference on ‘Illegal Science’. The purpose is to collect and discuss intriguing stories that trace the diversity of ‘Illegal Science’ through different times and places. I hope this post inspires you to participate in the conference to share stories you have come across.

I don’t want to bend the arc of suspense any further – let’s see how Haeckel triggered the banning of biology education in the Oberstufe, i.e. the final years of secondary education, of the majority of German[2] schools.

A man with a mission

When Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection reached Germany in the 1860 translation of On the Origin of Species, the German zoologist Haeckel was immediately sold. For him, evolution by natural selection would finally give a satisfactory scientific explanation of the origin of species. No supernatural deity or any other external force was needed – natural explanations were sufficient. Haeckel saw evolution as the basis for his science-based worldview. Away with the idea of species as fixed entities, away with the idea of man’s superiority, and away with religion! That was his mission and Haeckel wanted to spread his Weltanschauung to his German audience. The school, he thought, would be an apt point of departure. He proposed to immediately include evolution into school curricula – at the expense of religion (Kelly 1981,p.58; Trommer 1993, p.190).

The implementation of Haeckel’s wish, however, faced some serious problems. Two cases from the 1870s illustrate the tense atmosphere regarding the teaching of evolution; an atmosphere in which Haeckel became the epitome of a scientist with a ‘dangerous idea’.

The ‘Lippstädter Fall’

Hermann Müller (1829-1883), brother of the well-known biologist Fritz Müller (1821-1879), was a botanist and well-respected biology teacher at the Realschule 1. Ordnung[3] in the German city of Lippstadt. He became the main protagonist in what scholars have referred to as the ‘Lippstädter Fall’ (Depdolla 1939; Blumberg 1977a; Trommer 1993). Müller, convinced by Darwin’s idea of evolution by natural selection, began to incorporate Haeckel’s German works on evolution into his classes. He thought that an evolutionary view of nature, one in which all organisms are related, would be of the highest didactical value. Pupils would learn about the very natural (as opposed to supernatural) workings of the world. Next to Haeckel’s works, Müller also taught parts of Carus Sterne’s (1839-1903) Werden und Vergehen (1866), a book that was heavily criticized among conservatives due to its atheist tendencies.

It did not take long until Müller came under attack for using teaching material that seemed incommensurable with prevailing Christian views on Creation. A vendetta against him and his didactic methods began in different newspapers and by 1877, Müller was the personification of anti-Christian teachings in Prussian schools. His curriculum presented an aberration from the ethos of Prussian education. Schools were to raise moral, Christian citizens and not materialist atheists (Blumberg 1977a).

Müller was forced to respond. If he were to be convicted of openly declared contempt of the Christian belief, immediate dismissal from the teaching service would have been the likely consequence. Müller adapted his curriculum and sued the newspapers for libel and won (cf. Depdolla 1939; Blumberg 1977a; Kelly 1981).

Even though Müller could settle the case for his own career, the ‘Lippstädter Fall’ became a warning for teachers all over the Empire. The message: teach evolution and you might get into trouble.

Haeckel vs. Virchow

On September 18th 1877, Haeckel gave a speech entitled Die heutige Entwicklungslehre im Verhältnis zur Gesamtwissenschaft [Today’s theory of descent in relation to the overall sciences] at the Public Assembly of German Natural Scientists and Physicians. It was yet another moment for Haeckel to advocate the inclusion of evolutionary theory into school curricula.

During the same assembly, Haeckel’s former mentor and famous scientist Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902) took the floor to firmly warn against the inclusion of a mere hypothesis into school curricula. For him, evidence for the theory of descent, and especially of human animal descent, was too scattered. A speculative theory such as evolution had no place in the classroom of secondary schools.

Virchow’s refutation of Haeckel’s demand was not only built on scientific considerations, however. Virchow had another argument up his sleeve; an argument that would weigh far heavier than his scientific concerns. He claimed that the dissemination of Haeckel’s evolutionism could foster the propagation of socialism. Virchow’s argument referred to the rise of the Paris Commune in 1871, in which the proletariat organized itself against France’s conservative government. Virchow insinuated that the revolutionary power in Haeckel’s anti-aristocratic, anti-clerical, science-based statements resembled those uttered by the upset working class in France (cf. Blumberg 1977b; Di Gregorio 2005; Richards 2008)

Virchow’s attack against Haeckel, both on a scientific and political level, became a frequent topic in German newspapers (Blumberg 1977b). The media attention did not really come as a surprise; after all, the two famous scientists Virchow and Haeckel were battling over a topic that had interested regional and national newspapers for several months in the case of teacher Hermann Müller.

The ‘ban’

The teaching of evolution, of a dangerous idea, also became a topic of interest in the German Reichstag. In 1878, Prussian conservative Wilhelm Joachim von Hammerstein (1838-1904) brought the issue to the attention of his colleagues:

“But I have to say that if the teaching of Haeckel’s Darwinism is permitted in our schools, if it is allowed to inculcate our adolescent students with materialism, the education authorities are not attending to their duty. Then they will carry the responsibility if a generation arises in our nation whose credo is atheism and nihilism, and whose political orientation is communism.”[4] (Hammerstein cited in Blumberg 1977a, p.40)

The situation was tense. Atheism and socialism were both considered dangers to a strong German Empire. And evolution was seemingly a scientific theory that could further enable them to spread. The 1882 guidelines issued by the Prussian ministry of education reacted: biology as a whole was excluded from the final years of secondary education.

Evolution was not named as the reason for this decision. The guidelines merely stated that the discussion of certain theoretical hypotheses should be reserved for professional studies. Although no direct attacks against evolution can be found in the ministry’s decision, the result of the 1882 was in effect the elimination, thus ‘banning’, of evolution from the Prussian curriculum.

Haeckel openly criticized this decision (Haeckel 1889, p. 335), but he also largely profited from it. While no pupil could learn about evolution in the classroom, Haeckel could take over the role as ‘educator’. His popular books became a major source to educate the German public in evolutionary theory (Nordenskiöld 1936; Kelly 1981). During his lifetime, Haeckel even sold more books than Darwin. Worldwide. A German pupil remembered: “Who of us did then not carry next to the official New Testament an unofficial volume of Haeckel?”[5] (cited in Blumberg 1978, p.441)

Only in 1925, six years after Haeckel’s death, did biology, including evolution, become a mandatory subject in Prussian biology education.

Inspired?

If Haeckel’s story reminds you of something you have come across in your own research and you are interested in cases in which science is banned, in which scientific knowledge is hidden or in which certain directions of research are favored over others, you are exactly what we are searching for!

We are looking for people, academic and non-academic, to share stories and show the many facets of ‘Illegal Science’ in past and contemporary societies.

Interested in sharing a story and listening to others? Contact me at: constance.sommerey@gmail.com

o-o-o

Blumberg, B. (1977a). “Der ‘Fall’ Müller – Lippstadt (1877) und die Lehrplanänderung von 1882.” Biologie in der Schule 26(1): 38-43.

Blumberg, B. (1977b). “Haeckel und Virchow zur Entwicklungslehre in der Schule.” Biologie in der Schule 26(12): 538-542.

Blumberg, B. (1978). “Die Wiedereinführung des biologischen Unterrichts (1908) und die Anerkennung der Entwicklungslehre als Bildungselement der höheren Schulen.” Biologie in der Schule 27(10): 437-442.

Depdolla, P. (1939). “Hermann Müller-Lippstadt und der Kampf um den biologischen Unterricht.” Der Biologe 8: 216-221.

Di Gregorio, M. A. (2005). From Here to Eternity. Ernst Haeckel and Scientific Faith. Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Haeckel, E. (1889). Natürliche Schöpfungs-Geschichte. Gemeinverständliche wissenschaftliche Vorträge über die Entwicklungs-Lehre im Allgemeinen und diejenige von Darwin, Goethe und Lamarck im Besonderen . Berlin, Georg Reimer.

Kelly, A. (1981). The descent of Darwin: The Popularization of Darwinism in Germany, 1860-1914. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press.

Nordenskiöld, E. (1936). The History of Biology: A Survey (1920-24). New York, Tudor.

Richards, R. J. (2008). The Tragic Sense of Life. Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Trommer, G. (1993). Natur im Kopf. Die Geschichte ökologisch bedeutsamer Naturvorstellungen in deutschen Bildungskonzepten. Weinheim, Deutscher Studienverlag.

[1] „Nehmet Eure Kinder in acht!“

[2] In this text, I will refer to the developments in Prussia. The other German states, at times, followed a slightly different path. The history of biology education in the entire German Empire is, however too complex, which is why Prussia, as the largest and arguably most influential German state during that time, will serve as an example.

[3] ‚Realschule‘ is a form of secondary education in the German school system. In the time period under study, graduates of the Realschule were eligible for tertiary education in the natural sciences.

[4]„Aber das muß ich sagen, daß, wenn es zugelassen wird, daß der Haeckel-Darwinismus einen Lehrgegenstand auf unseren Schulen bildet, wenn es erlaubt ist, den jugendlichen Schülern unserer öffentlichen Lehranstalten den Materialismus einzuimpfen, dann tun die Schulaufsichtsbehörden ihre Pflicht nicht. Und dann tragen sie die Verantwortung dafür, wenn in unserem Vaterland eine Generation heranwächste, deren Glaubensbekenntnis der Atheismus und der Nihilismus, deren politische Anschauung der Kommunismus ist“.

[5] „Wer von uns trug damals in seiner Schultasche neben dem offiziellen Neuen Testament nicht inoffiziell seinen Band von Haeckel?“