What is an expert? Is it someone who possesses specialized knowledge? Or rather someone who is qualified to make rational decisions on sensitive social issues, a technocrat perhaps? Is it someone with great technical skills, who uses these skills professionally? For historians, the different markers used to typify a class of ‘experts’ pose considerable difficulties. As historians of the sciences and political historians increasingly examine the way in which the rise of experts since the middle of the nineteenth century was tied up with the advent of modernity, they also seem to lack a proper (and shared) terminology to tackle such a complex phenomenon. How to conceptualize ‘expertise’ in historical research? How to examine experts as actors of historical change?

Recent scholarship in the history of science and science studies has shown that the ‘expert society’ was never fully within the hands of the experts themselves. Their success, as Martin Kohlrausch and Helmut Trischler have shown in their recent synthesis, cannot be understood apart from the development of the modern European states, which relied heavily on a new army of experts.[1] Since the late nineteenth century, state expansion generated an increased demand for technical and scientific knowledge, while at the same time, processes of specialization and professionalization expanded the ‘supply side’ of expertise and legitimated expert intervention into new areas. These large-scale processes were at the heart of experts’ rise to fame. And they are still very much reflected in the representation of experts as specialists, professionals or technocrats.

Yet historians have equally pointed to the problem of agency that results from viewing expertise as the outcome of large-scale dynamics. For if expertise was largely brought about ‘on demand’, as an answer to the specific needs of the state, what then with experts’ agency as individuals? To what extent did they shape their own advisory roles? Historians of science have addressed this matter by scrutinizing the processes of legitimization that underlie expert authority. Even if structural developments were beyond experts’ reach, their recognition as experts still depended on their own ability to convince others ‒ state officials, fellow scientists and the general public ‒ of their knowledge and skills. These insights have led historians to abandon the notion of ‘technocracy’, which focused too exclusively on the (one-sided) relation between politicians and experts. Instead, expertise has been said to depend on the mutual recognition within and outside the academy, in between state and society. Much work, however, remains to be done. We have yet to grasp why experts were so successful in some social domains, while they became so easily defeated in others.

Performing Expertise

One place to look for inspiration, might be the recent work in the sociology of science. Sociologists, in fact, faced a similar challenge of attaining a more complex understanding of experts’ authority. But they had a different ambition in mind: the ambition to create theoretical models of experts’ interactions with their audiences. In constructing such models, sociologists have redefined the ‘technocratic’ interaction between specialists, politicians and the public in terms of ‘expert performances’ ‒ an approach that allows to pay more attention to the strategies used by experts to convince their audiences. Typical of this approach was Stephen Hilgartner’s Science on Stage in which he studied the apparatus through which science advisers gained credibility. Science advisers, in Hilgartner’s view, inspired confidence among government officials by displaying trustworthiness and competence through their rhetoric and comportment.[2]

Such attention to performance might also inspire historians interested in studying modern expertise. It may draw new attention to the different ways in which experts played into their audiences in the past. More than a matter of specialized knowledge or skills, expertise becomes a problem of embodiment in this way ‒ the embodiment of a specialist role, and a set of scientific and social ideals connected to it. By disentangling expertise in terms of experts’ role-playing vis-à-vis different audiences, this approach has the potential to reveal some of the particularities and ambiguities of experts’ function in modern liberal-capitalist societies. It may, in particular, help develop at least three central features of what scholars are increasingly calling a new form of ‘technoscientific’ expertise.

Expertise and Modernity

The first of these features concerns the scientific grounding of expertise. In formulating claims of objectivity, modern experts increasingly stressed the use of scientific methods and applied a scientific terminology. Such claims were strengthened by new institutional affiliations. Expert knowledge became increasingly legitimized by disciplinary communities, institutionalized at universities and in scientific societies, to which experts belonged. Besides state officials or the broader public, one’s specialized colleagues also constituted a necessary audience for aspiring experts ‒ an audience that required particular strategies. The Dutch sociologist Wiebe Bijker has recently conceptualized experts’ performances to these different audiences as a form of mediation between ‘front stage’ (to meet with politicians) and ‘backstage’ (to discuss with one’s colleagues).[3]

A second feature of modern technoscientific expertise is its political and institutional embeddedness. The expansion of government intervention into ever more areas of social life thoroughly reshaped the pre-conditions within which advisory roles were to be performed. Through their intense affiliation with government institutions, modern experts became an integral part of power structures, assuming full-time positions in state service as decision-makers, organizers and managers. This shift, however, also produced new problems of credibility and independence. How could experts provide neutral advice to government officials, so critics argued, when they were on the payroll of these same men? Here lie the historical roots of the ambiguous position (and in some cases distrust) of experts in modern society.

A related paradox emerged because of the growing entanglement of expertise and political ideologies ‒ a third feature of modern expertise. The very conviction that science could carry through social changes – a conviction which led to the ‘scientization of politics’ ‒ made that modern experts increasingly grounded their authority in a positivist ideology and became players in the political arena. Yet, in moving from advisers to reformers in this way, experts increasingly became part of politically inspired movements. Such engagement was at odds with their claim of transcending party politics by implementing scientific views on social problems.

These features, and the ambiguities at which they point, illustrate the advantages of a broader conceptualization of expertise ‒ as an embodiment of a specialist role and a set of ideals connected to it. Its strength lies in its more open approach of expertise, which is no longer loaded on beforehand with the meanings that underlie experts’ characterizations as technocrats, professionals or specialists. Attention to performance instead opens up the question of how experts themselves shaped their advisory functions. Such research may benefit from recent gains in the sociology of science. Unlike sociologists, however, historians should not establish models of expertise, but rather use sociological understandings of expert performance as tools to conceive of experts as actors of historical change, while acknowledging their dependence on circumstances beyond their reach.

Further reading

Joris Vandendriessche, Evert Peeters and Kaat Wils (eds.), Scientists’ Expertise as Performance. Between State and Society, 1860-1960 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2015).

o-o-o

Joris Vandendriessche is a postdoctoral researcher at the research group Cultural History since 1750 at KU Leuven. His research interests concern the history of the medical sciences, public health and health care in the nineteenth and twentieth century. In his doctoral research, he studied the history of medical societies in nineteenth-century Belgium and published particularly on their role in the development of modern scientific expertise and scientific publishing. Currently he is writing a history of the Leuven academic hospitals in the twentieth century.

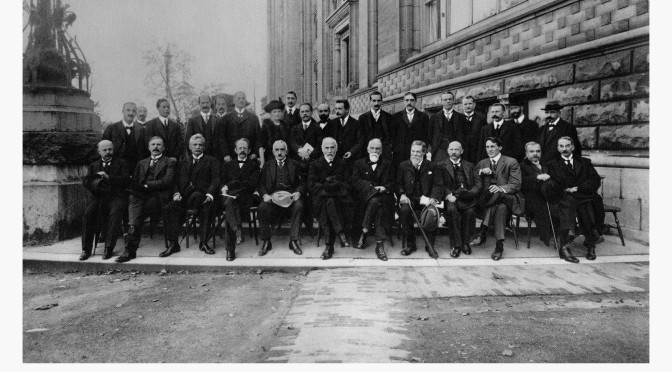

Image: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cb/Solvay_conference_1913.jpg

[1] Martin Kohlrausch and Helmut Trischler, Building Europe on Expertise: Innovators, Organizers, Networkers (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[2] Stephen Hilgartner, Science on Stage: Expert Advice as Public Drama (Standford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000)

[3] Wiebe Bijker, Roland Bal and Ruud Hendrickx, The Paradox of Scientific Authority. The Role of Scientific Advice in Democracies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).