All screwed up

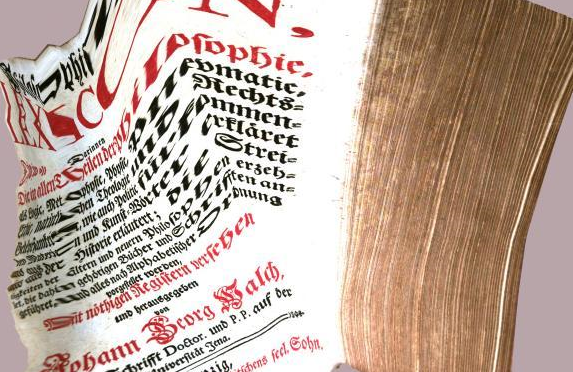

Not long ago I looked up an eighteenth-century philosophical lexicon on Google Books. The unevenly numbered pages looked like this (image 1):

It looked to me like a work of art: an open book with disfigured words. The words are not only taken out of perspective, but appear completely distorted. Some of them are almost torn apart: only one or two letters are readable, or even visible. The flat page suddenly gains virtual depth by being folded: the text has acquired a third dimension, but that has not helped in making it legible. The hierarchy of grammar has been supplanted by the hierarchy of visual perspective. The text has a new focus: halfway, on the left hand side of the image, there is a point, a summit almost, where the flanks of the text meet. A large O (of the word Ordnung, i.e., ‘order’ – how ironic) dangles just below this peak, to the left. At first, I thought the point carried the world ‘viel’ (much), but when I compared it to a scan of another copy of the same book, also available, luckily, on Google Books (image 2), it turned out to be the word ‘Lexici’ (which is recognizable, in parts, at three different places – Le-, Lexic- and Lexici – although it appears only once on the page, in line four; are these three images put together?). It is preceded by the words ‘Der Form eines’, i.e. ‘the shape of a lexicon’. What irony! Is this scrambled image the actual shape of a lexicon? The philosophical wordplay of this mishap just cries out to be examined! One can decipher the word ‘Alphabet’ at the top right, and above it, in Greek letters, ‘Platonikon’. Artistic, linguistic, and philosophical self-reference? The thing we are staring at just now is the very opposite of the Platonic idea of a book. Or is this idea of the book in fact not metaphysical, but physical: after all, the distorted image makes the philosophies in the words completely inaccessible to us, and instead just confronts us with the physicality of their medium.

The rest of the book, to the right, is closed: it turns its back to the reader, curving into itself. Many thin leaves of paper in fact seem to have pushed and crumpled the only visible page.

The art of words and philosophy

There are two sides to this failed scan. One is artistic, the other is social. The first image on the scan of this book looks artistic indeed (image 3).

There is a ruler, which makes me think of a Formula 1 chequered flag. Or is this perhaps a chess or checkers ribbon? Where does that blue come from? Is this a book caught at some bizarre moment of being washed over by a wave of blue ink?

And look at the beautiful title page (image 4). We can read the word ‘sophie’ but ‘philo’ is too disfigured to be discernible. This is a lexicon, a dictionary explaining what words mean, but it has ruptured its most important word: love of wisdom has lost its love. Wisdom is all that is left. And what is this wisdom? That a book first needs to be distorted in order to convey wisdom?

What a wonderfully miscarried scan! Every single page provokes disconnected reflections on the nature of words, books, philosophy: a postmodern kaleidoscope of references and associations. From a reader, I turned into an observer. The book draws attention to its own physicality precisely through the impossibility of its digitalized shape. It raises the question of how these books are scanned.

Who pushes the button?

An executive of the Royal Library in The Hague once described to me the enormous logistics involved in the Google Books project: once in a while, a great Google truck came to the Royal Library, it was loaded with books (in what must have been an insurance nightmare), which were then taken to some factory-like building where dozens of employees turn the pages and push the buttons.

Occasionally buttons are pushed too eagerly, for example when pages are still in movement, or when a tightly bound book slips from a human hand and stubbornly closes itself, or when a human hand is still busy turning a page. Scans made at such moments tear apart the image of the text. A digitization failure like this reminds us of something we are usually unaware of when the process goes smoothly: with Google Books, we loose the sense of materiality of a book. Much of its physical condition gets lost in digitization.

But the people who make the images of the books are likewise lost in digitization. Again, it is only with failed scans that we get a glimpse of fingers, stuck in pink plastic gloves or covers, like finger-condoms, holding down the pages. Suddenly, we are reminded of the physicality of the digitization process: in order to make words endlessly reproducible on our millions of screens, they first have to be made virtual by the action of anonymous hands. It reminds me of what Robert Darnton wrote about one of the cheaper editions of the famous encyclopedia of Diderot and D’Alembert: the monstrous size of the project forced labourers to speed up: ‘A close examination of any set will reveal a profusion of workers’ finger prints, over inked pages, misfolded sheets’ (The Business of Enlightenment [1979], 274).

Now that those eighteenth-century typographers have turned into fossils, what does the work of modern text-reproducers look like?

ScanOps: Google books’ miscarriages turned into art

Someone working at Google Books in California asked himself this same question. His name is Andrew Norman Wilson. He tried to interview the workers who do the scanning. They are at the bottom of the Google corporate food chain. Google employees count four classes: each layer of workers is marked with its own colour-code. The lowest class, known as ‘ScanOps’, do the manual digitization work. They wear yellow badges, which means that they have no perks. Unlike the others, for example, they are not entitled to receiving paid lunches or to ride the Google Bikes, and they are not allowed access to Google buildings apart from their own working place, barring them from any social interaction with other employees of the “Google Campus”. These workers are mainly people of colour: men and women who are black or of Latin-American descent. Wilson was fired after attempting to interview this lowest class of employees. His inquisitiveness was tantamount to breaking Google security rules, because the digitizers are not allowed to speak to anyone about their “extremely confidential” work (and, perhaps even more importantly, about their working conditions). You can listen to Wilson’s story on YouTube: “Workers leaving the Googleplex”.

Black and minority ethnic people, then, are the ones who do this mind-numbing manual labour for the preservation of what is mostly Western cultural history. It’s post-colonialism all over again. It brings to mind sweatshops, like the ones I always imagine to exist in the Philippines, where cheap labourers manually type out whatever needs to be digitized better than automatic optical character recognition (OCR) allows. I have this mental image of a factory hall of women, each behind her screen, typing out shiploads of books in English or German or French all day. The less they are familiar with the language, the better: then they type what they see, not what they read. They type simultaneously, and their versions are automatically compared and merged, filtering out their unavoidable typos. That’s how good-quality searchable texts of books which were not born digital are made available to the world.

And so it is with Google: disembodied minorities, forced into anonymity and silence, in disadvantaged conditions, do the manual labour. The books (as long as they are in the open domain, of course) are free for everyone in the world with Internet access to consult, but does the information and ideas they convey set the world free? The whole Google Books project is fraught with painful ironies, if not with social sarcasm.

Back to art

Andrew Norman Wilson found a creative outlet for his obsessions with Google Books. He took Google Books scans and adopted them: framed them in such a way as to form works of art. Often he extended the body parts, suggesting a greater visibility. But the individuality of the people they belong to remains hidden from us. What we see is some kind of cross-over between body parts and rectangular Mondrian-like art, with lots of blue and pink (image 5).

You can see these fascinating works of art on the website of Wilson’s project ScanOps (scroll down on that page for larger images).

Is there anybody (or any body) out there?

The old man-made book, now scanned by partly but hardly visible humans, reminds us that a book is a work of art, which involves not just the mental action of the author, but the labour of typesetters, of the designers of covers and title pages, of people working in badly lit cellars and in sweatshops far away from our own desks. Those scrambled pages, resulting from mistakes in a hidden process, betray that they have to work very, very quickly. Are you there, heroes? Or are you people lost in digitization? In complete anonymity you are doing an incredibly terrific job in making my scholarly life easier. Can I shake your hand to thank you? Or am I forced to merely contemplate your digitized fingers? Surely, there is a comic serendipity to words: ‘digitus’, after all, is Latin for finger.

(I’m indebted to Jeroen Bouterse, Ivan Flis and Niall Hodson for their remarks).

o-o-o

Dirk van Miert works at Utrecht University as a historian of knowledge. He specializes in the history of the Republic of Letters.