This past year I began writing a book on the conception and regulation of environmental carcinogens. Central to my project is the emergence of risk as the main category for understanding the hazards of low-dose exposure to suspected carcinogens. Risk became more than either a medical or financial term. In fact, it mediated between them. In the 1970s and 1980s, risk-benefit analysis emerged as a key tool for regulatory decision-making, taking into effect the economic costs as well as the health advantages of reducing hazardous exposure to chemical substances in air, water, foods, drugs, and consumer products. Ulrich Beck, more than any other social scientist, shaped the critical literature on risk. In an age of nuclear power and environmental contamination, he offered a penetrating and ultimately pessimistic assessment of high-technology society.

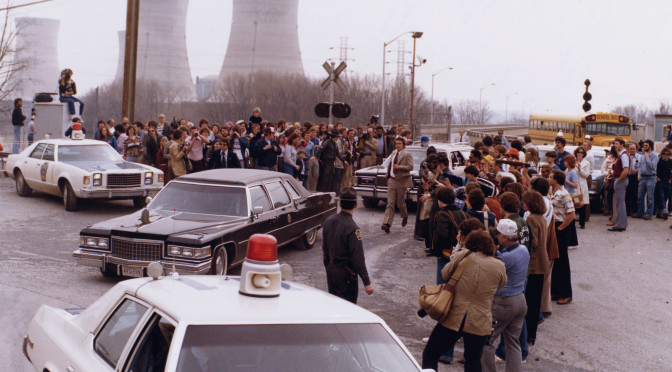

Beck passed away in January, which spurred me to reread his work. His book Risikogesellschaft was in press when the Chernobyl reactor meltdown occurred in 1986, which followed on the heels of the Three Mile Island accident, the Bhopal disaster, and the explosion of the Challenger Space Shuttle. By the time Risk Society was published in English, in 1992, it was read largely as a commentary on these technological accidents, above all Chernobyl. This did not require an imaginative leap, for Beck had already pinpointed radioactive and environmental contaminants as the key uncontrollable hazards he had in mind. As he states:

By risks I mean above all radioactivity, which completely evades human perceptive abilities, but also toxins and pollutants in the air, the water and foodstuffs, together with the accompanying short- and long-term effects on plants, animals and people. They induce systematic and also irreversible harm, generally remain invisible, are based on causal interpretations, and thus initially only exist in terms of the (scientific or anti-scientific) knowledge about them.[1]

For Beck, risks are based in material realities, but cannot be abstracted from social negotiations. “They can thus be changed, magnified, dramatized or minimized within knowledge, and to that extent they are particularly open to social definition and construction. Hence the mass media and scientific and legal professions in charge of defining risks become key social and political positions.”[2] For Beck risk is both real and constructed, and the tension between these two aspects runs through the book.

Part of what I find so compelling about Risk Society is its insistence that technology is entangled with privilege. As Beck observes, “some people are more affected than others by the distribution and growth of risks.”[3] In fact, he represents social inequalities as having shifted from being centered on wealth to being centered on risk. Or, as Brian Wynne and Scott Lash have put it, “an older industrial society, whose axial principle was the distribution of ‘goods,’ was being displaced by an emergent ‘risk society,’ structured, so to speak, around the distribution of ‘bads.’”[4] Class stratification is not undermined but rather reinforced—and replaced—by one’s risk group. Even so, the privileged in Beck’s world cannot shield themselves completely from the risky by-products of technology. Experts and the safety systems they design are ultimately incapable of preventing (or even predicting) disasters, and when a technological catastrophe happens, it affects everyone. Beck refers to this as the “boomerang” effect. Technology bites back.

In short, Beck depicts technology’s dangers as outpacing the ability of experts to control them. In this sense, his Risk Society echoes the dystopic books and films of the era, in which high-tech accidents threaten human existence. This technophobic genre is well-illustrated by Michael Crichton’s Andromeda Strain and Jurassic Park, though The China Syndrome, a film released 12 days before the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, is surely the exemplar. Beck’s account, however, is neither drama nor exposé, but a nuanced social critique. Upon rereading his book, four features stood out to me as distinctive and worthy of further reflection. They are both characteristic of their time, and part of its legacy for the present moment.

First, Beck’s risk society is a thoroughly secular society. Threats such as shipwreck, famine, or fire can only be “transformed into calculable risks” in a non-Providential world. As Beck notes, François Ewald made the case that with the invention of insurance a provident state emerged.[5] The chance of nature was tamed by calculations of risk. In turn, the proliferating insurance system—and its counterpart, the welfare state—relied on seeing society, too, in terms of risk groups. At the same time, other aspects of society that were previously naturalized—family size, upbringing, gender roles—became viewed as social. What is significant about this for Beck is the burden it places on individuals for making sound decisions about reproduction and childrearing, rather than following traditional (often religious) expectation. Bad outcomes are then the result of poor decisions or lifestyle choices. For Beck this social transition reflected secular modernity, which was inexorably replacing earlier institutions and religious beliefs in the West.[6] Yet events of the last thirty years have raised questions about the inevitability of secularization, an issue Beck himself grappled with in his later book World at Risk. There he says that risks themselves are culturally situated, reflecting world views: “Some people view the al-Qaeda terrorism through religious spectacles and see it as confirming prophecies of the Apocalypse; for others, risks enter the world stage only after God has made his exit.”[7] Beck describes the debates over terrorist activities as a “clash of risk cultures.” He focuses on how the post-9/11 society tries to manage new risks by anticipating and “staging” them. I take his point, but am not sure he reckons sufficiently with the importance of religious beliefs in prompting terrorist activities and well as shaping responses to them.

Second, the hazards that pervade Risk Society are not contained by national borders. Beck points to the transboundary diffusion of pollutants to argue that “Risk Society in this sense is a world risk society.”[8] This is an issue that he develops further in World at Risk, noting at the outset that environmental problems supersede both national boundaries and political alliances. Global crises bring countries into an often-uneasy relationship. Nations find they are fated to a common future even if they have not had a common past. As Beck puts it,

National and international politics (under certain circumstances also transnational economic enterprises) are not liberated from all need to act by fate of theoretical uncontrollability; rather the, global public discourse of risk puts the screw on them to justify themselves and to take action. They are condemned to respond. This expectation of responses presupposes the counterfactual hypothesis of controllability even when all available response models fail.[9]

For Beck, globalization concerns the circulation of contaminants as well as goods, and he views the environmental crises spawned by technology and trade as inherently unmanageable.

Third, Beck seems to be a scientific realist even though he is highly critical of science and technology. This creates a conundrum about the status of expertise. For Beck, there is “genuine, real, physical riskiness” in large-scale technological systems.[10] The scientific rationality behind these systems undermines itself, by being unable to predict or deal with the unintended consequences of accidents and contamination. Expert judgment is also corruptible. Beck observes that industry, attempting to divert blame from their responsibility for technologically-generated problems, will invariably use ‘counter-science’ to “bring in other causes and other originators,” relying on the media for help.[11] However, Beck’s reference to false scientific conclusions (p. 68) indicates that he is not a relativist as far as knowledge is concerned.[12] As fallible as experts may be, they hold the keys to scientific reality. Only experts can certify risk. As Brian Wynne has shrewdly observed, there is no room in Beck’s picture for lay expertise, in which ordinary people can best understand the changing conditions of their environment and intervene.[13] Beck does, nonetheless, appreciate the runaway effects of fear in Risk Society—definitions of risk have “social effects” that become unmoored from their “scientific validity.”[14]

Ultimately Risk Society rests on an inescapable dilemma: high-tech industry cannot contain the negative externalities—especially environmental degradation—it generates. Yet this diagnosis itself relies on scientific evaluation, particularly regarding the ecological consequences of industrialization. Thus science is implicated in both producing and recognizing technology’s shortcomings, while being unable to reverse them. One can certainly blame experts for promising more than they can deliver. As Brian Wynne puts it, “science inexorably tends to refute itself as its culture of scientism creates false claims and expectations in society at large.” But in my view, neither Beck’s nor Wynne’s views leave sufficient space for the vagaries of scientific uncertainty. Assessing risk is scientifically elusive as well as socially fraught. This adds one more complication to risk and expertise. There are limits to scientific knowledge of environmental contamination and its consequences for human health that make risk assessment a highly uncertain venture. In turn, economically interested parties often mobilize this uncertainty to shape public opinion and thwart government regulation.[15] Science thus becomes implicated in the genesis, diagnosis, and obfuscation of risk. Whereas I share Beck’s pessimism that experts can ultimately fix the environmental problems of late modernity, I attribute this, more than he did, to the inherent limits of scientific and medical knowledge.

My fourth and final reflection picks up a quite different theme in the book. Beck pays careful attention to other aspects of late modern life, especially the organization of the family. Most commentators on Risk Society focus, as I have here, on Part I of the book, appropriately entitled “Living on the Volcano of Civilization: the Contours of Risk Society.” But in Part II, which concentrates on the theme of individualization, Beck examines how technological and economic changes have put pressure on the family, and on sexual relations. His analysis of gender roles was very much of its time, particularly in emphasizing the battle of the sexes, but its insights remain pertinent. As he observes:

The spiral of individualization is thus taking hold inside the family: labor market, education, mobility—everything is doubled and trebled. Families become the scene of a continuous juggling of diverging multiple ambitions among occupational necessities, educational constraints, parental duties and the monotony of housework. The type of ’negotiated family’ comes into being, in which individuals of both genders enter into a more or less regulated exchange of emotional comfort, which is always cancellable.[16]

I find this portrait of intimate relations in late industrial society as haunting as his depiction of invisible environmental hazards. For Beck, the forces of the labor market and welfare state act directly on the individual, and this explains (pace Marx) the emergence of capitalism “without classes” yet riven with social inequalities.[17] I’m not convinced that Beck’s “spiral of individualization” provides sufficient conceptual glue to hold together such disparate elements of modern life as family dynamics and technoscientific risks. Yet I cannot but admire his attempt. Although Beck is no longer with us, it is clear that his Risk Society is, and will be for a long time to come.

o-o-o

Angela Creager is the Thomas M. Siebel Professor int he History of Science at Princeton University and serving President of the History of Science Society. Books by her hand include The Life of a Virus: Tobacco Mosaic Virus as an Experimental Model, 1930-1965 (2002) and Life Atomic: A History of Radioisotopes in Science and Medicine (2013).

[1] Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity, trans. Mark Ritter (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 1986), p. 22. All quotations (including italicization) are from this English version.

[2] Ibid., pp. 22–23, all italics original.

[3] Ibid., p. 23.

[4] Bronislaw Szerszynsky, Scott Lash and Brian Wynne, “Introduction: Ecology, Realism and the Social Sciences,” in Scott Lash, Bronislaw Szerszynski, and Brian Wynne, eds., Risk, Environment and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology (London: Sage, 1996), pp. 1–26, on 2.

[5] François Ewald, “Insurance and Risk,” in Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon, and Peter Miller, eds., The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), pp. 197–210.

[6] For a broader discussion of this theme, see Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2007).

[7] Ulrich Beck, World at Risk, trans. Ciaran Cronin (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009), p. 21.

[8] Beck, Risk Society, p. 23.

[9] Beck, World at Risk, p. 31.

[10] Szerszynski, Lash, and Wynne, “Introduction,” p. 7.

[11] Beck, Risk Society, p. 32.

[12] Ibid., p. 68.

[13] Brian Wynne, “May the Sheep Safely Graze? A Reflexive View of the Expert-Lay Knowledge Divide,” in Lash, Szerszynski, and Wynne, Risk, Environment and Modernity, pp. 44–82.

[14] Beck, Risk Society, p. 32.

[15] David Michaels, Doubt is Their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010); Robert N. Proctor, Golden Holocaust: Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011).

[16] Beck, Risk Society, p. 89.

[17] Beck, Risk Society, p. 88.