When the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède died in 1825, fellow naturalist Georges Cuvier lamented this as a loss for the field of natural history. Lacépède, who authored the five-volume Histoire naturelle des poissons, ‘had a talent for finding the appealing side of the story of these organisms [fish] that seem to touch us so little and do not arouse our imagination’.[1] Might fishes’ uninspiring feel, as Cuvier mentions, be the reason that the field of ichthyology (the official term for the study of fish) has not been systematically studied in contemporary research into natural history – quite unlike early modern founding publications on botany and ornithology?

This neglect is certainly in contrast with the esteemed placed that the study of aquatic creatures actually held in early modern and modern Europe. For example, illustrated fish books appeared earlier than that of other fields in zoology, and both in number and volume ichthyological publications surpass contemporary zoological publications.[2] My research, which is part of a broader NWO project, aims to study the ways in which European ichthyology was shaped as a field of expert knowledge during the ‘long eighteenth century’, spanning from the 1680s to the 1820s.

From the sixteenth century onwards thick ‘fish books’ were written, containing descriptions often accompanied by lavish illustrations.[3] Some of these could literally contain fish: the Leiden botanist Johannes Fredericus Gronovius (1686-1762) developed a method to preserve actual dried fish in a book, resulting in a ‘fish herbarium’ similar to the more widely known and used plant herbaria.My project studies both the various fish books written in the eighteenth century as well as their authors, comparing and contrasting the different emphases they placed in their ichthyological research. This may best be made clear by focusing on one species, the porpoise – which is now placed in the mammal class, but for a long time was considered a fish and therefore studied by ichthyologists.

On porpoises

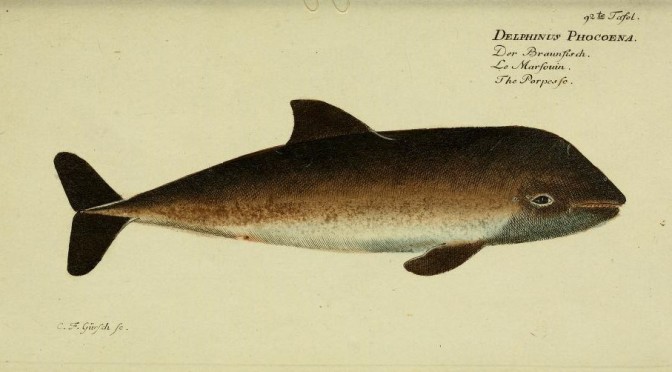

The Cambridge parson naturalists Francis Willughby (1635-1672) and John Ray (1627-1705) were pioneers in classifying fish not according to habitat, but based on physical features only. They also offered the first anatomical descriptions of the porpoise’s airways; this proved to be useful for understanding the regulation of breathing in the order of cetaceans. The Swede Peter Artedi (1705-1735), whose notes were published by Carl Linnaeus in 1738, further developed a system in which fish species were categorized. His description of the porpoise counts a little over one hundred words and gives brief and standardized descriptions of the fish’s features. Some decades later, the German naturalist Marcus Eliezer Bloch (1723-1799) published a fish book that contained very precise, hand-colored drawings, which could include gold, silver or bronze in order to imitate the shimmer of scales. Lifelike representations of nature as these may have facilitated identification and classification of species. The Frenchman Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707-1788), intendant of the Jardin du Roi in the decades before the French Revolution, took to a more variable, narrative style of describing animals in his natural history – a style adopted by his collaborator, the aforementioned Lacépède (1756-1825). In his report on the porpoise, Lacépède incites astonishment and wonder: a description of the fish’s physical features is followed with an ode to the porpoise’s artful natation.[4]

Books describing the same kinds of species could thus be noticeably different in their treatment of these, so that debates on classification and categorization ensued. Since the approaches that these authors unfolded both shaped and were shaped by changes in the field of natural history, this project also considers how descriptions were contextually informed. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw an increasing importance of collections and scientific institutions, as well as an growing interest in maritime exotica. Furthermore, naturalists’ works were influenced by matters of patronage and institutionalization, as scientific expeditions both local and global in their span were issued. Taking these matters into account, this project proposes to fill the current lacuna in research on the development of the study of the aquatic realm in the long eighteenth century.

Header image: Illustration of a porpoise from Bloch’s Oeconomische Naturgeschichte der Fische Deutschlands vol. 3 (Berlin, 1784)

o-o-o

Didi van Trijp is a PhD candidate in the project ‘A New History of Fishes: A Long-Term Approach to Fishes in Science and Culture, 1550-1880’. This project is based at Leiden University and supervised by prof. dr. Paul Smith. Co-supervisor of the ‘Enlightened Fish Books’ subproject is prof. dr. Eric Jorink.

[1] Georges Cuvier, Historical Portrait of the Progress of Ichthyology from its Origins to Our Own Time, edited by Theodore W. Pietsch and translated by Abby J. Simpson (Baltimore, 1995) 164

[2] The publication in rapid succession of four richly illustrated works on fishes epitomizes the role of ichthyology as scientific avant-garde within early modern zoology: Belon (1551), Salviani (1554), Rondelet (1554) and Gessner (1558).

[3] The term ‘fish’ here should be understood in its early modern sense, covering the whole range of aquatilia. According to this way of classifying species based on their habitat, hippopotami and mermaids were included in earlier fish books too.

[4] ‘Il joue avec le mer furieuse. Pourroit-on être étonné qu’il s’ébatte sur l’océan paisible, et qu’il se livre pendant le calme à tant de bonds, d’évolutions et de manoeuvres?’ M. Lacépède, Histoire naturelle des cétacées vol. 2 (Paris, 1809) fol. 214