As historians, we historicize. Indeed, it is our firm belief that everything in our world is open to historical analysis and that, in the case of a job well done, the result will invariably be a deeper understanding of the object of our study. In fact, the more timeless and placeless this object appears to be, and therefore the more immune to historical analysis, the more interesting the outcome has often proved to be. We now have histories of ‘the modern fact’, ‘objectivity’, and of ‘truth’, that is to say precisely those aspects of science that one tends to see as universal and timeless. In this essay I would like to advocate a similar approach with regard to another notion that most scientists tend to take for granted, that of the ‘laws of nature’. To be more precise, I want to suggest three possible lines of attack that may deepen our understanding of this crucial concept, and therefore of science itself. The first aims at a conceptual history of the term, akin to what the Germans call ‘Begriffsgeschichte’; the second is a study of the ‘biography’ of specific laws, and the third looks at the distribution of such laws across the various disciplines. Strangely enough, many of these topics have so far barely been addressed by historians of science.

A conceptual history

Most historians who did take an interest in the ‘laws of nature’ focused on the roots of this conception. Although these reach back into antiquity, the few concrete examples of specific uses of the term ‘law’ as applied to nature before 1600 can be found in what was known as ‘mixed mathematics’, in particular optics. However, as John Henry has convincingly argued, it was Descartes who gave the laws of nature a central place within natural philosophy. In this respect Boyle and Newton followed him closely. In practice, all three of them tended to equate the laws of nature with the laws of motion, the fundamental rules to which the Divine Lawgiver had subjected the particles of matter. As Boyle put it, ‘the casual justlings of atoms’ could never have given rise to ‘this goodly and orderly Fabrick of the World’. Both the social and the natural order were seen to depend on laws imposed upon their constituents, be it human beings or particles.

In the seventeenth century, then, neither ‘Boyle’s law’ nor ‘Kepler’s laws’ were known as such. It was not until the eighteenth century that natural philosophers such as ‘s Gravesande, like Descartes a lawyer by training, came to broaden the use of the term, so as to also include other kinds of generalities, among which Newton’s ‘law of gravitation’. As Vermij has pointed out, the Dutch Newtonians, following Newton and Cotes, stressed a voluntarist reading of the laws of nature. Whereas Descartes derived the laws from God’s immutability, they emphasized the contingency of the laws, which were seen to have flowed from God’s arbitrary and unfathomable Will. Only empirical research would enable the philosopher to reveal such laws. This stance contradicted the notion of a small number of truly fundamental rules (such as the laws of motion) and allowed for a more general interpretation and application of the label ‘law’.

Whereas we have ample reason to believe that the search for laws of nature became more and more central to the business of natural philosophy, culminating in well-known claims by Herschel, Whewell, Helmholtz and other mid-nineteenth-century luminaries of the primacy of the laws of nature, few historians have studied this development in detail. Nor have we studied the way that natural philosophers conceived of the nature of such laws, how such views gradually secularized, and how these laws were seen to relate to natural philosophy’s traditional quest for causal explanation.

In fact, the latter question occupied many early modern philosophers. At times, Boyle questioned whether brute matter could really ‘obey’ laws. Didn’t such obedience require intelligence? Could a ‘law of nature’ then be more than a mere metaphor that simply expressed the ways God invariable acted in this world? Hundred years later the influential Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid came to distinguish ‘physical’ causes, such as ‘laws of nature’, from ‘efficient’ causes. Also in his view true agency required intelligence and a will. Accordingly, the study of efficient causation in nature belonged to natural theology, rather than natural philosophy. The ambiguous causal status of laws of nature seems to have been a constant through much of their history.

An example of the changing religious bearings of the laws of nature is the conception of Divine ‘creation by law’. When in the course of the nineteenth century more features of nature were seen as the product of historical change, rather than of a single act of creation, the notion that God created in time through the ‘agency’ of His laws became increasingly popular. It more or less bridged the gap between an instantaneous creation and secular views of evolution. This brings us to the question how the shift from natural philosophy to modern science affected the view of laws and their causal import.

The most virulent attack on the inclination to reify the laws of nature was delivered by Ernst Mach. In his view the concept of the ‘laws of nature’ simply derived from the projection into nature of the human psychological need to find one’s way in nature, and therefore to find simple and pleasing patterns. In general, however, it seems that the concept easily survived the loss of its religious underpinnings. Laws, now seen as fully autonomous, have remained part of nature itself. In a sense they are judged to be epistemologically prior to concrete events. To explain an observed fact means to incorporate that fact into a general law. Still, there is some evidence, to be addressed below, that the laws of nature have not survived the process of secularization unharmed. For now, we can conclude this first of our three perspectives by emphasizing that a general history of the laws of nature still needs to be written.

Specific laws of nature

Moving to our second perspective – or from the general to the specific -, we may also pose the question when, how and why a particular rule came to be seen as a ‘law of nature’. Most rules or patterns in nature did not receive this label. Why we have come to privilege certain rules over others is not always clear and may well depend upon several historical contingencies. As yet, probably no one can tell when and how Boyle’s law became ‘Boyle’s law’ or Hooke’s law ‘Hooke’s law’. Google N-gram suggests that most eponymous laws acquired their names in the nineteenth century. National rivalries may well have influenced this process (e.g. ‘Boyle’s law’ vs. ‘Mariotte’s law’), as well as the urge to raise the status of natural philosophy by honouring its main representatives. The rise of eponymous laws in the early nineteenth century may also have been connected to the change in sensitivity with regard to ‘scientific discovery’ around 1800, as pointed out by Simon Schaffer in a classic paper.

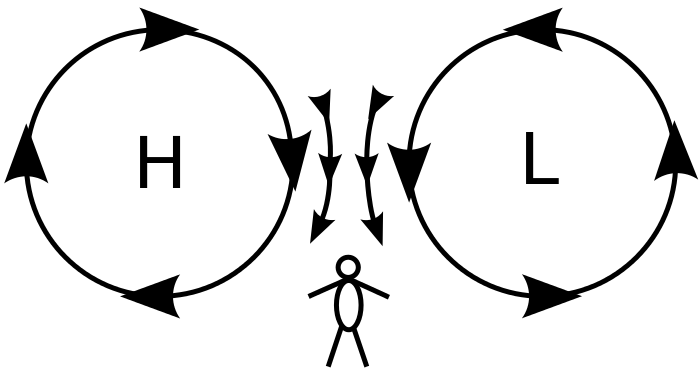

When in the course of the nineteenth century the possession of laws became the hallmark of a mature science, aspiring disciplines acquired a strong interest in producing and showcasing their own laws. One of these emerging disciplines in the nineteenth century was the burgeoning field of meteorology. Azadeh Achbari and I have recently tried to answer the simple question how a local rule of thumb, proposed by the Dutch meteorologist Buys Ballot in 1857, was transformed in the course of ten years into a widely acknowledged meteorological ‘law’, known in several languages as ‘Buys Ballot’s law’.

As it turns out there is an intricate story behind this transformation. It revolves around the misgivings of the British scientific elite about the British practice of storm warnings, based upon practical experience rather than laws. When they finally succeeded in ending these ‘unscientific’ practices, vigorous public protests soon forced the Britons to resume the storm warnings. To avoid a loss of face, the meteorological office needed to come up with a ‘scientific’ basis for doing so. This predicament created a strong demand for a meteorological ‘law’. Such a law was eventually found in Buys Ballot’s wind rule. After the prestigious Royal Society had sanctioned the rule with the new designation ‘Buys Ballot’s law’, other scientists rapidly followed suit.

Another example of new ‘laws’ which served various interests can be found in the introduction of Mendel’s laws in the early twentieth century. Carl Correns, who first coined the term ‘Mendel’s law’, primarily did so in order to take away the priority of ‘discovery’ of the newly found patterns from his rival Hugo de Vries. William Bateson, who used the same expression, advanced the law in competition with ‘Galton’s law’ (although he would later speak of ‘Mendel’s principles’). It was Thomas Morgan to whom we owe the current expression ‘Mendel’s laws’ as well as their content. In his case, the introduction of a second law also served some personal interests.

Behind these specific interests, however, we can also distinguish a shared interest: the creation of a new discipline. These early Mendelians were eager to isolate the study of heredity from related and overlapping branches of biology by construing a new kind of life science that was both experimental and exact. The central position of mathematical laws in the new field helped to distinguish and sever it from biology, which clearly lacked such laws. It is telling that Bateson baptized the new discipline ‘genetics’, suggesting a greater kinship to exact sciences such as mathematics and physics than to biology and geology.

Disciplinary differences

This example brings us to our third perspective and a new set of questions. How does the introduction and use of ‘laws of nature’ differ in different disciplines? It is clear that from the start the use of the word law in natural philosophy was more or less restricted to mathematical laws, such as Coulomb’s laws, Ampere’s law, Weber’s law, Avogadro’s law, Gay-Lussac’s law, Charles’s law, Gauss’s law et cetera. They accordingly abounded in the emerging discipline of physics and were rare – or even absent – in the life sciences during much of the nineteenth century. There is a lot of talk of laws in Darwin’s Origin of Species (‘laws of variation’, ‘laws of inheritance’, ‘laws [of] the conditions of existence’, ‘laws of the correlation of growth’, ‘laws of resemblance of the child to its parents’, ‘laws of palæontology’), but these laws were either considered to be still unknown or simply left unspecified. None of them acquired textbook status. Eponymous laws did not emerge in biology before the twentieth century.

In these regards there is an interesting discrepancy between general talk of the laws of nature, where the concept is often used in a very broad meaning, and concrete instances of such laws, where the concept is usually restricted to mathematical cases. Such inconsistencies cry out for a deeper explanation and therefore for serious research. Whatever the outcomes of such research, it may tell us something about hierarchies and power structures within the emerging world of science and, possibly, also about the changes in such relationships. In this regard, the Mendel case is highly suggestive.

Taking a more diachronic perspective, a remarkable feature is the sudden disappearance of eponymous laws around 1900 within the discipline of physics. In twentieth-century physics general principles are still named after their supposed originators, but they are no longer called ‘laws’. We have ‘postulates’, ‘principles’, ‘equations’, ‘inequalities’, and so on, but no new ‘laws’. This is a clear sign of a meaningful change within physics. So what does it symbolize? The conclusion of the gradual shift from natural philosophy with its religious overtones to a fully secular (modern) physics? The emergence of theoretical physics as a branch of physics? Or the realization that even the hardest scientific laws – Newton’s laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation – were at best approximations?

Conclusion

In general, there is a remarkable discrepancy between the vast amount of literature about laws of nature produced by philosophers of science, and the scarcity of books and papers by historians. So far, all the issues raised above have hardly been touched upon by historians of science. I hope to have been able to show that this neglect is regrettable. Even simple digital means, such as the search engine of Google Books, allow us address many of these questions without even leaving our office desk. It is fairly easy to find out when a new label starts to catch on and to follow its spread into new geographic areas. Apart from their intrinsic interest, the questions addressed above may also provide a venue towards a better understanding of more general aspects of natural philosophy and modern science, and, perhaps most of all, the shift from the former to the latter.

Literature

Ernst Mach, ‘Sinn und Wert der Naturgesetze’, in: Erkenntniss und Irrtum (Leipzig 19173), pp. 449-463.

Edgar Zilsel, ‘The Genesis of the Concept of Physical Law’, The Philosophical Review, 51 (3) (1942), pp. 245-279.

Simon Schaffer, ‘Scientific Discoveries and the End of Natural Philosophy’, Social Studies of Science 16 (3) (1986) pp. 387-420.

John Henry, ‘Metaphysics and the Origins of Modern Science: Descartes and the Importance of Laws of Nature’, Early Science and Medicine 9 (2) (2004), pp. 73-114.

Gideon Yaffe, Manifest Activity: Thomas Reid’s Theory of Action (Oxford 2004)

John James Macintosh, Boyle on Atheism, (Toronto 2005), on p. 371.

Jonathan Marks, ‘The Construction of Mendel’s Laws’, Evolutionary Anthropology 17 (2008), pp. 250-253.

Lorraine Daston & Michael Stolleis (eds), Natural Law and Laws of Nature in Early Modern Europe: Jurisprudence, Theology, Moral and Natural Philosophy (Burlington 2008)

Rienk Vermij, ‘Defining the Supernatural: The Dutch Newtonians, the Bible and the Laws of Nature’, in: Eric Jorink and Ad Maas (eds.) Newton and the Netherlands. How Isaac Newton was Fashioned in the Dutch Republic (Leiden 2012), pp. 185-206.

Azadeh Achbari & Frans van Lunteren, ‘Dutch Skies, Global Laws: The British Creation of

‘‘Buys Ballot’s Law’’’, Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, 46 (1) (2016), pp. 1–43.