Thinking about nineteenth-century scholars we tend to picture well-behaved members of polite society. The paintings and pictures of old faculty members that still adorn so many contemporary university halls and lecture rooms show earnest and erudite men who seem to be miles above ordinary pettiness. Some of these men have indeed made extraordinary contributions to their fields of research. Few of them, however, were above an ubiquitous practice that is often seen as hopelessly petty: gossiping.

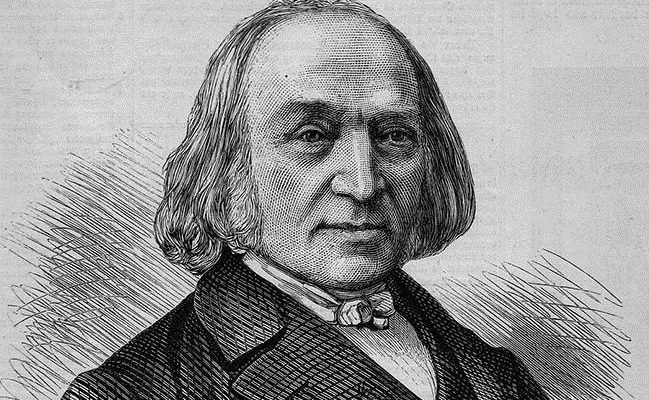

In fact, gossip could and often would be a major influence on academics daily work experience and their relations with their peers, as the example of the continuous stream of gossip about the Göttingen Old Testament scholar and orientalist Heinrich Ewald (1803-1875) shows.[1]

One of Ewald’s most unpleasant character traits was his propensity to rudeness and bossiness. Especially his junior colleagues suffered from this. Therefore it might come as no surprise that the initial joy about a teaching job alongside his old teacher quickly left Ewald’s former student Theodor Nöldeke (1836-1930) once he experienced these traits at close. His letters to his Leiden friend Jan de Goeje (1836-1909) are full of complaints about the uneasiness of working with Ewald: “[Ewald’s] manifold discussions of ‘higher’ religion etcetera are indeed unpleasant … If I didn’t have to take Ewald into account, I could conduct myself more freely in regard to those issues.”[2]

Nöldeke had hoped that his own research would benefit from the presence of his old and knowledgeable teacher. However, he ended up disappointed and sharing his frustration with De Goeje: “I have a lot to talk about with you. I am sure you can explain a lot of excerpts in my Arabic poems that I cannot deal with … [I] don’t have anyone here, whom I can ask for advice … For more than one reason I cannot discuss it with Ewald.”[3]

Nöldeke’s ongoing complaints about Ewald illustrate some of the important functions that gossip can have. In the first place, it may have been a case of simply letting off steam. Secondly, and maybe more importantly, it served as a way to cement both the personal and the professional relationship between him and Jan de Goeje. The men would continue to stay friends and closely cooperating colleagues until the latter’s death in 1909.

In the 1860s Nöldeke and De Goeje were both young men facing the same challenges in making an academic career. They did not, however, only exchange letters with members of their own generation. The éminence grise of German orientalism, the Leipzig Arabist Heinrich Leberecht Fleischer, recognized their talents and cultivated his relationship with these promising young men. One recurring topic in his letters was the obnoxious behavior of Ewald. In his comments about Ewald’s evaluation of his colleagues in his own personal journal, the Jahrbücher der biblischen Wissenschaft, he criticized both his rude condemnations of his peers and his pompous writing style, that reminded him of the language of the Old Testament prophets: “In the end we fully owe it to his magnanimity and forbearance only, that we quasi-scholars still exist; if he would like to destroy us, it would cost him, like the JHWH of the Old Testament, just a whiff of his mouth and we would be gone!”[4] In this same sneering vein Fleischer also referred to Ewald as the ‘Pope’ or the ‘Buddha’ of Göttingen.

In other words, Fleischer’s badmouthing of Ewald in his letters to younger colleagues was not just a way of letting off steam or cementing personal bonds. His gossip served a third function. Through his confidences Fleischer, one of the main gatekeepers of the professional community of orientalists, set out group norms while suggesting that Nöldeke and De Goeje met these standards. In this way he signaled that they were accepted into his peer group.

Gossiping even served a fourth function: it was a way to share information. It especially served this function in Fleischer’s letters to his younger colleagues. Through Fleischer’s condemnations of Ewald, Nöldeke and De Goeje would find out what was expected of them if they aimed to further their academic career. The rejection of Ewald’s self-presentation as some kind of ‘Prophet’, ‘Pope’, or ‘Buddha’ combined lessons about the expected characteristics of scholarly production and the desirability of certain character traits. The repudiation of Ewald’s high-minded writing style suggested that solid scholarly work should focus on accuracy, thorough research and exhaustive source references rather than fanciful imagination and literary tours de force. At the same time, the criticism on his overly harsh evaluation of his colleagues suggested that a good scholar had to relate to his peers in a more benevolent and supportive way. Especially the dissemination of this sort of comments about the disposition and character of a respectable scholar depended on the very private way of communication that we often call gossip. After all, a public repudiation of Ewald’s character would exactly be the sort of rudeness that Fleischer tried to warn against!

Even if gossip was one of the things that shaped the working experience of men like Nöldeke, De Goeje, and Fleischer, sometimes it was, of course, just a somewhat childishly malicious practice for its own sake. So let me close with a fine example of this malice, an awkwardly patronizing comment that Nöldeke made to De Goeje about the Sanskritist Max Müller after his death: “The best thing about him, except for his delicate sense of form and his poetic skill, has always been his wife.”[5]

[1] This case is discussed more extensively in: Christiaan Engberts, “Gossiping about the Buddha of Göttingen: Heinrich Ewald as an Unscholarly Persona,” History of Humanities 1, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 371-385. DOI: 10.1086/687973.

[2] Theodor Nöldeke to Jan de Goeje, April 27, 1861, BPL 2389, Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden (hereafter UBL).

[3] Theodor Nöldeke to Jan de Goeje, June 17, 1863, BPL 2389, UBL.

[4] Heinrich Leberecht Fleischer to Jan de Goeje, March 11, 1865, BPL 2389, UBL.

[5] Theodor Nöldeke to Jan de Goeje, June 6, 1902, BPL 2389, UBL. Emphasis in the original.