From high-tech gadgets to views of distant planets and meteors, scientific discoveries often spark our imagination. We might almost forget that imagination has an important role in the scientific enterprise itself too. This is particularly true for those subjects that little else can give us access to. We can employ telescopes, probes and microscopes to study the geological make-up of the earth, bacteria or distant planets. But what if we want to study objects that no instrument can reveal? This was a central issue in seventeenth- and eighteenth century discussions of the history of the earth. In order to understand Creation, the building of the Ark or Noah’s flood, early modern natural philosophers had to rely for a large part upon their imagination, which they guided through visual material. This is the starting point for the research project Imagining Earth, conducted at the VU Amsterdam: how does one study that which cannot be seen, and how did early modern natural philosophers imagine the earth? This post explores the role of imagination in natural philosophy, comparing it to modern ways of understanding earth and cosmos.

Imagining Earth

At first sight, it might seem as if this print is a modernist piece of art, perhaps an early form of Malevich’s Black Square. However, it is part of the 1617 Utriusque Cosmi Historia, by the English alchemist Robert Fludd. It is with this print that the chemical philosopher presents the darkness at the beginning of time, and it is followed by several more prints on the subject. To me, this is the most spectacular part of his entire work: it tells the viewer that the best way to understand creation might be by imagining it, by visualizing – perhaps even experiencing that vast, infinite darkness. To study something that cannot be seen, one must find a way to make it accessible to the mind – and that is precisely what this print does. For Fludd, an alchemist, the image seems to have fulfilled the same role as an experiment, re-creating Creation on paper. In this case, however, the image is to spark a reaction in our minds: it aims to incite the imagination, the bridge between the senses and divine insight. It tells us that, if we want to understand the creation of the earth, we must imagine it; and in this case, this is a visual act.

Other philosophers awarded a similar role to the imagination. Francis Bacon, for instance, believed it was imagination that ordered our sense-perceptions, making it the faculty of creativity.[1] According to Bacon, however, this also meant that the faculty of imagination was the place where ‘cognitive errors’ originated. Most philosophers approached the topic with similar ambiguity. Thomas Hobbes, for example, considered the act of thought to be ‘a train of imaginations’.[2] And René Descartes famously downplayed the role of imagination. Without discarding it entirely, he believed the intellect to be free of sensory interference, and therefore truer.[3] It is this stance that characterizes most philosophers who write on the topic: not so much a mistrust of the imagination, but rather an appraisal of the faculty of reason.[4]

In some cases, an acceptable way of guiding reason in order to make claims about reality is through instruments. It has been suggested that it was instruments that were able to bridge the gap between the senses and the understanding, without running the risk of fabrication.[5] They make accessible objects of knowledge that we cannot touch with our hands or see with our eyes, from distant planets to the cells in our body.

But what if we want to study those things which can never be seen, even with the strongest of telescopes? In order to make empirical claims about phenomena such as Creation or the Deluge, one needs to imagine these in natural philosophical terms. Having been the subject of debate for centuries, seventeenth-century scholars approached these issues in an entirely new way: no longer as purely theological or historical occurrences, but as events that could be investigated through natural philosophy. While imagination and images have a role in all types of science, the relationship between observation, image and imagination has to be reassessed in those cases where simple observation becomes nigh impossible. Rather than turning to a purely conceptual discussion, natural philosophers felt the need to approach these topics in the same way as they would, say, plants or animals. In order to make this approach possible, they used printed images to substitute for reality. These images are based mostly on the imagination, however, rather than on sensory observation.

A small example out of a multitude of cases: in his Joodse Oudheden, ofte Voorbereidselen op de Bijbelse Wijsheid (1690), the seventeenth-century Dutch biblical historian Willem Goeree relied upon natural philosophical ideas to understand Creation. By imagining the earth as a ball composed of layers (water, solid earth, the Abyss, etc.) and drawing this in pictures, he was able to draw several conclusions. It is by imagining this development of the earth in visual terms that the concept of earth itself was formed. This led him to conclude, for instance, that mountains were the result of the Deluge: the vast amount of water necessary to flood the earth was contained inside the planet, and when it burst out of its container, it destroyed the surface, creating mountains in the process. This conclusion relies upon imagining the earth as a vast ball as seen from space, which is a visual act. In order to do so, Goeree used a visual style which he has borrowed from Thomas Burnet (author of The Sacred Theory of the Earth, 1684), and through Burnet from René Descartes (Principia Philosophiae, 1644), and indirectly also from Athanasius Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus, 1676. All four authors imagined the earth through the same ideal cross-section, allowing the mind to form a mental image along the lines of printed materials. The imagination, here, became the basis upon which the image was produced, as well as a mediator that allowed reason to understand the process under investigation.

Visual images have always played an important role in the ‘modern’ discipline of geology, to the extent that it has been described as “amongst the most visual of sciences”.[6] Surprisingly, although ideas about the history of the earth have changed quite dramatically over the past few centuries (few geologists would still say mountains emerged as a result of Noah’s flood), the mode of representation of these images presents a relative continuity. The Goereean cross-sections of the earth, themselves inspired partly by maps of mines and drawings by Descartes and Kircher, were taken over (through the works of later-eighteenth century proto-geologists and cosmographers) by geologists such as Von Humboldt, whose ‘vertical cartography’ cuts the earth in half the same way as earlier images. Geology has used this mode of representation ever since: whether it’s for studying volcanoes, strata or the development of continents, the cross-section is an important mode of geological thought.

Imagining Space

Is imagination, then, only reserved for imagining earth? On the contrary! From the geological perspective that cuts the earth in half, we now turn to the Apollonian view, in which we see the earth and other planets as if we were floating through space. The representations by early modern Earth theorists have not only inspired geologists, but cosmologists too. This is part of a desire to experience not only our own planet, but others as well: if only we could see these planets, they would become real.[7]

In early modern times, the imagination served to understand other planets as actual places. Goeree, for instance, muses on the existence of humanlike life on other planets: to see these planets through a telescope, is to know that they are similar to earth and must therefore contain life. Today, knowing that mankind has already set foot on the Moon, we ask ourselves not only what distant planets are composed of, but how we would experience them if we were actually there. While this kind of imagination has been around since at least the nineteenth century, it is only during the last few decades that astrophysicists have been able to produce photographic representations of distant planets. Starting with the moon-landing of the Russian Luna 3 in 1959, visual material of distant bodies became available, providing a unique experience of a place so distant, yet so understandable in earthly terms. From then on, visual material has allowed scientists to understand space in an entirely different way – but it also raised the stakes, as the new material opened up new options for and posed new challenges to extra-terrestrial imaginations.

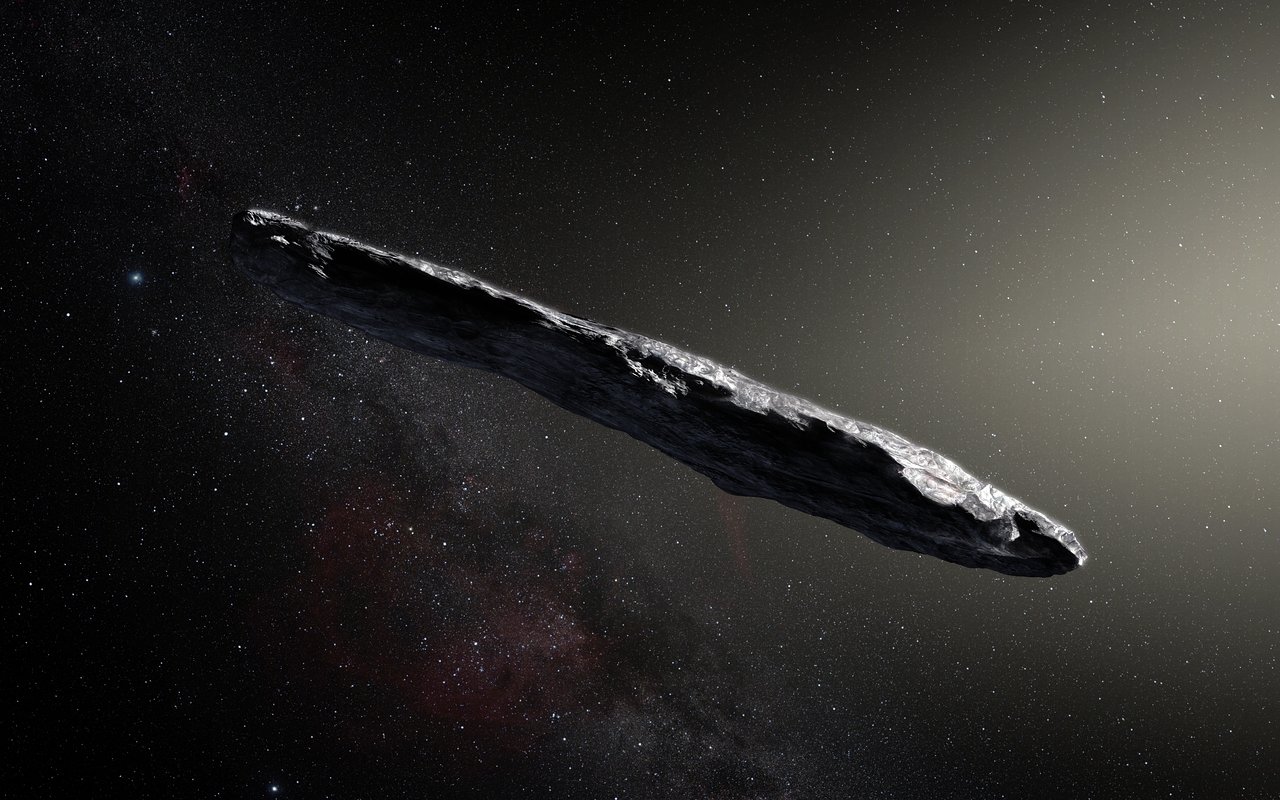

One only has to look at the myriad artist impressions of far and distant planets to see that the imagination plays a central role in our understanding of the cosmos. In the case of early modern earth-philosophy, the image is a way of investigating our planet. Today, however, imagination seems to serve another goal. Even without any knowledge of what the surface of a planet looks like, artists can ‘imagine’ the planet and provide us with a sense of what it might look like. The goal of these images is to allow the public to awe and to dream, not to convey accurate knowledge. In these images, “a healthy level of speculation is allowed,”[8] meaning that colors and continents can be made up and the laws of gravity don’t matter. They walk a fine line between sparking interest in the science of space and giving people the wrong idea of what space might look like. “You can make stuff in such extraordinary detail, people might think it’s real. People might think we’ve actually seen these features”.[9]

With the arrival of ‘hard’ photographic ‘evidence’, the role of imagination in the practice of science might seem to have run its course. However, I would argue that these images are only the next step in our imagination of the unseen. Photographic evidence does not end the role of imagination; it simply changes the rules to which our imagination must adhere. One way of interpreting the pictures taken by satellites is through our imagination. Photographs provide the fuel for an imagination that is just as rich as early modern musings on planets, one that relies upon instruments and serves as a tool with which one can process their feedback. Whether it is mediated through prints, photographs or video, imagination is central to those branches of the scientific enterprise that deal with things unseen.

‘A rare view of the surface of a comet’, shots taken by European Space Agency’s Rosetta Probe. Via YouTube/Financial Times.

o-o-o

[1] Thomas Hankins, Instruments and the Imagination (1999) 3-7. Sorana Corneanu, Koen Vermeir, ‘Idols of the Imagination: Francis Bacon on the Imagination and the Medicine of the Mind’, Perspectives on Science 20,2 (2012) 183-206.

[2] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, volume I, chapter 3.

[3] John Cottingham, A Descartes Dictionary (1993) 84.

[4] For an accessible overview: John Cottingham, Rationalism (London, 1984).

[5] Hankins, Instruments, 3-7.

[6] Cathryn Manduca, David Mogk eds., Earth and Mind: How Geologists Think and Learn about the Earth (GSA Special Papers, volume 413, 2006) 157.

[7] See for instance Denis Cosgrove, Apollo’s Eye – A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination (Baltimore, 2001).

[8] New Atlas, ‘Artist’s Impression: How are Planets Painted’, 18 april 2016, https://newatlas.com/how-are-planets-painted/42763/

[9] National Public Radio, ‘Out Of This World: How Artists Imagine Planets Yet Unseen’, 24 october 2016, https://www.npr.org/2016/10/24/495072203/out-of-this-world-how-artists-imagine-planets-yet-unseen.