The Dutch care so much about their delta. When widespread use of the word delta unexpectedly increased in the specific geographical area of the Netherlands, we can now speak of an epidemic.1 I am jesting, of course, but there is a more serious problem: the Netherlands are hardly a delta and the connotations that come with the word are potentially misleading. This is more than a semantic issue – it is about public understanding of the relation between the natural formation of the lowlands and their present use. In what aspects are the Netherlands a delta? When did this frequent usage of the word delta emerge? Did this happen gradually or was it introduced with a purpose? In what way is this usage causing problems in climate adaptation and mitigation?2

The word delta is often associated with the Delta Works in the Zeeuwse Delta (the Zeeland province in the southwest), which attract admiring tourists from all over the world.3 The Dutch boast that God created the Earth but the Dutch created Holland. It is Dutch policy to keep their fame and flame burning by exporting their Delta Technology to help defend other deltas worldwide against river floods and the sea and to change wild rivers into usable shipping fairways.4

Within the Netherlands, the word is also contagious. There is a municipality called Eemsdelta (bordering on the Eems estuary in the Wadden Sea near the Dutch-German border), since the turn of the century three water authorities were created with delta in their name (Waterschappen Drents Overijsselse Delta, Hollandse Delta and Brabantse Delta) and a national Delta Program with a Delta Commissioner labours to prepare the Dutch for future effects of climate change.5 It does not end here. Great plans carry the name Delta, such as the Delta Plans for the biodiversity crisis, pancreatic cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, animal farming and many more problems as a quick search on the internet will show. In the summer of 2024 the Delta Climate Center will be opened in Zeeland.6

Wherein are the Dutch lowlands a delta?

As is well-known, the term delta was coined by Herodotus for the Nile north of Gizeh where it branches out. This area resembles the capital letter delta and was formed from sediment deposited on the shore of the sea where the water slowed and lost the capacity to carry the sediment. In contrast, a river mouth where sediment is predominantly moved by the tides (ebb and flood) is called an estuary. The capacity of the tides to move sediment and form land is seen in sea arms such as the Eastern Scheldt and in the Wadden Sea.7 To be sure, if we define a delta as an area where a river enters the sea through several river branches, then the lowlands are a delta formed by the rivers Western Scheldt, Meuse, Rhine, Vecht and Ems. If we define a delta where river arms split and drop sediment, then the area in the triangle Emmerich-Den Bosch-Utrecht is a delta of the Rhine and the area northwest of Kampen is a delta of the IJssel (a branch of the Rhine). However, most of sediment (sand and mud) stored in the lowlands, including the dunes and beaches, came from the sea. Moreover, the greater majority of the lowlands did not form by sedimentation by from the built up of dead swamp plants.8

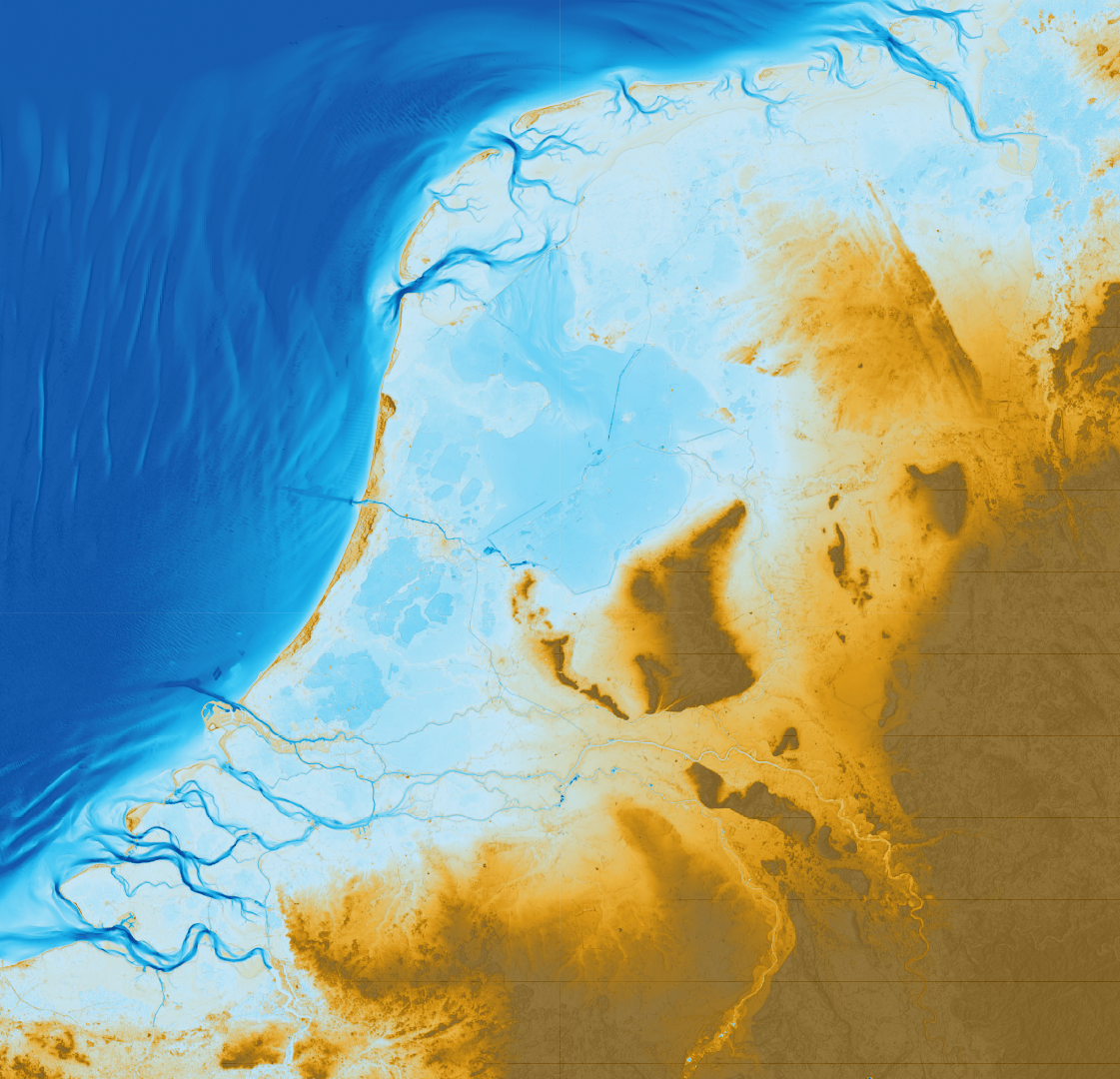

Even if a small part of the lowlands were formed as delta, it no longer functioned as such following the construction of dikes in late medieval times. Dikes allowed continuous water table lowering for agriculture and building. Consequently, the dead plants decayed, the land subsided and many devastating river and coastal floodings followed. Large areas excavated for peat were also lost and could only be regained by continuous pumping (notice the large areas below sea level on the elevation map in Figure 1).9 A large part of the lowlands has now sunk several meters below mean sea-level and continue to subside today due to continued water management.10 In short, the lowlands formed as a swamp, which, due to a thousand years of water management and peat excavation, lowered to several meters below mean sea-level.11

No use for the word delta in eighteenth century river hydraulics

Until the end of the eighteenth century, Dutch surveyors and others concerned with rivers and river mouths did not use the word delta. Cornelis Velsen (1703-1755), a surveyor who wrote an often-cited treatise on the Rhine and Meuse rivers, did not use the word even once in it, despite a brief discussion of the river mouths of the Danube delta and Nile delta.12 Based on antiquarian research and conjecture, Velsen developed a theory that sedimentation in the river branches, in relation to ebb and flood, and hence shallowing, caused the disastrous floods of his lifetime and before. Additionally, the Leiden professor Johan Lulofs (1711-1768) argued that both river sedimentation and the tides formed the lowlands. He further argued that sea-level rise and soil compaction caused the relative lowering of the land and bolstered this claim with references to historical evidence and river sediments in the subsurface of the lowlands.13

Christiaan Brunings (1736-1805), the first Inspector-General of Rijkswaterstaat, worked on river flooding and sedimentation problems as well as coastal problems.14 He nowhere used the word delta but, in his analysis of the depth and sedimentation problems of the rivers and sea arms, Brunings also refers to the tidal flows of ebb and flood like Velsen and Lulofs.

One could argue that the word delta refers to the larger scale of lowlands with all its river branches, and that Brunings, Velsen and Lulofs were mainly concerned with more local problems. However, all three link the floodings and sedimentation issues of all the river branches in close connection. As they (mistakenly) believed that sedimentation caused the flooding problems that were particularly intense in the Little Ice Age and before, all these authors used the word decay, or deterioration (‘bederf’).15

Deltas seen as loci of sedimentation in nineteenth century geology

In the early nineteenth century the word delta began to be used for the river mouths in the Netherlands.16 Perhaps this use was caused or helped on by the well-read 1830 Principles of Geology by Charles Lyell (1797-1875), where delta is mentioned hundreds of times.17 For Lyell, a delta is where mud and sand are deposited to advance new land upon the sea (Chapter XI) and he used the volume of the deposit to estimate the geologic age of these systems.18 In contrast, Lyell sees the waves and tidal currents as destructive, antagonist forces of the river. His first example in the chapter on the action of tides and currents is the Rhine, for which he describes how the forces of the river mouths, which formed a delta in the past, gave way to that of the sea (Chapter XX).

Lyell frequently mentions estuaries in his Principles but does not juxtapose this concept clearly to deltas. On the one hand he cites the geographer and oceanographer Major James Rennell (1742-1830), who called estuaries ‘negative deltas’ to indicate that estuaries are dominated by the destructive forces of tides and, unlike deltas, do not form land by sedimentation, but on the other hand Lyell mentions estuarine deposits that form below the water surface, suggesting that estuary refers mainly to the channel where the tides are at play whereas delta refers to the larger-scale landscape including the former river channels that were silted up. Here, Lyell uses findings of marine shells and pebbles as evidence. The debate surrounding what comprises a delta and an estuary continues today and differs between the geomorphology and geology disciplines, but the use of the word delta for the Rhine and Meuse may have stuck.19 Perhaps the perceived channel sedimentation problems thought to have caused floods in the Rhine and Meuse was associated with delta, instigated by Lyell’s frequent use of the word.

The power of the word delta in the twentieth century

After the 1953 floods, the Delta Plan may have triggered a more frequent use of the word delta for the Dutch lowlands.20 However, the word delta did not immediately replace terms such as river mouth, estuary and sea arm. The Delta Plan was at first called Land Reclamation plan by its main author, Johan van Veen (1893-1959) and only just after the 1953 floods was the advisory Delta committee installed with van Veen as secretary.21 The 1958 Delta Law used the word delta in quotation marks and explained that the severely flooded Zeeland province with the Western Scheldt estuary and the sea arms would be informally called the ‘delta area’.22 A decade later, Rijkswaterstaat still left no doubt of its understanding of the nature of the lowlands: “The Ems, the Rhine, the Meuse and Scheldt, all run into the sea on the Netherlands territory. The estuarial region of the latter three rivers is known as the Delta area and it is here that […] Rijkswaterstaat is carrying out the Delta Project.”23 Rijkswaterstaat points at the dominant role of the tides in the estuaries and sea arms in the southwest and is at pains to point out that this area “is known as the Delta area” in passive voice. Clearly, this has changed in the past fifty years, but why?

I suggest this is more than mere fashion: there was a political motivation to call the Dutch lowlands a delta. After years of fruitless warning against weaknesses in the flood defenses by van Veen, the Delta Plan needed selling to the government and the public. Over the past decades Rijkswaterstaat increasingly adopted a double role of responsibility for politically neutral policy implementation on the one hand and managing its legitimacy on the other.24 In its latter role, there was a need for convincing terminology to sway stakeholders to agree with plans for expensive and unpopular spatial planning.

Perhaps ‘Delta Plan’ sounds powerful, whereas people are rather unlikely to be swayed by a plan called Bog Proposition, Mire Program or Swamp Stratagem.25 Bog, mire and swamp are in use as verbs with negative connotations in both Dutch and English language. Yet a swamp it is and a bog it was: the lowlands are an excavated bog and a subsided swamp near the end of its usability.

Conclusion

By framing the lowlands as a delta with the capacity for further sedimentation, the existential crisis of climate change and future sea-level rise are kept small in public discussion. Civil engineers waste no time to claim that higher dikes and big dams will keep out the sea and the river floods. This approach contributed to make the Netherlands one of the safest places to live in worldwide, but the comparative silence about causes of increasing flood magnitude and certain sea-level rise and other sources of slow disasters brought upon the world does not mean that such disasters will stay ‘not in my backyard’ (NIMBY). Nearly needless to preach to this choir, framing the lowlands as a strong river delta instead of a vulnerable coastal swamp reinforces the conflict between the immediate needs of the Dutch and their elected governments and the long-term need for equally nonneutral, unpopular, expensive and urgently needed spatial planning changes for climate adaptation and mitigation. It is to be hoped that the reader henceforth lives well in the swamp.

- Source of definition https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/epidemic-endemic-pandemic-what-are-differences. Google ngrams showing an increase after WWII: https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=delta%2Cestuary&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=en-2019&smoothing=2. ↩︎

- As the reader may have noticed from the tone of first paragraphs, there are many more problems that I will not address here, such as the utilitarian view on land use and the colonial perspective on applying delta technology in other countries, both of which contribute to long-term problems such as human-induced climate change, the biodiversity crisis and the rapid loss of coastal land, for example in tropical deltas with dammed rivers and mangrove forests removed for fuel and shrimp farms. ↩︎

- The Dutch engineers rewrote their history after the world-famous Delta Works, a series of dams and barriers constructed between 1954 and 1997. Following a devastating flood in 1953, the Delta Plan of Johan van Veen was executed. Van Veen was an engineer in Rijkswaterstaat who already warned for a disaster like this before WWII but was not taken entirely seriously. Today he is one of the heroes of the Dutch civil engineers. ↩︎

- See, for example, https://www.government.nl/topics/water-management/water-top-sector/delta-technology and https://tkideltatechnologie.nl/organisatie/, the Water Envoy who operates internationally https://www.government.nl/topics/water-management/waterenvoy and https://themasites.pbl.nl/future-water-challenges/river-basin-delta-tool/ as an overview of deltas and their problems worldwide. ↩︎

- https://www.deltaprogramma.nl/ ↩︎

- https://deltaclimatecenter.nl/ ↩︎

- De Haas, T., Pierik, H. J., Van der Spek, A. J. F., Cohen, K. M., Van Maanen, B., & Kleinhans, M. G. (2018). Holocene evolution of tidal systems in The Netherlands: Effects of rivers, coastal boundary conditions, eco-engineering species, inherited relief and human interference. Earth-Science Reviews, 177, 139-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.10.006 ↩︎

- See Peter Vos e.a., Atlas van Nederland in het Holoceen (Amsterdam 2018); https://www.cultureelerfgoed.nl/onderwerpen/bronnen-en-kaarten/overzicht/paleografische-kaarten. Also see C. Kruit (1963). Is the Rhine delta a delta? Verh. Kon. Ned. Geol. Mijnb. Gen. Geol. Ser., 21, 259-266. ↩︎

- The St Elisabeth Floods of 1421-1424 AD is the most famous example of land loss caused by human-induced subsidence. See Kleinhans, M. G., Weerts, H. J., & Cohen, K. M. (2010). Avulsion in action: reconstruction and modelling sedimentation pace and upstream flood water levels following a Medieval tidal-river diversion catastrophe (Biesbosch, The Netherlands, 1421–1750 AD). Geomorphology, 118(1-2), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.12.009 ↩︎

- See the national subsidence map: https://bodemdalingskaart.portal.skygeo.com/portal/bodemdalingskaart/u2/viewers/basic/ ↩︎

- When I explained this to Delta Commissioner Peter Glas during the 28 October 2021 lustrum meeting of the Vereniging voor Waterstaatsgeschiedenis, he finished the joke: “So I should be called Swamp Commissioner.” See https://www.waterstaatsgeschiedenis.nl/tijdschrift/2021-2/ ↩︎

- Cornelis Velsen (1749). Rivierkundige verhandeling (Treatise on river hydraulics), afgeleid uit waterwigt- en waterbeweegkundige grondbeginselen, en toepasselyk gemaakt op de rivieren, den Rhyn, de Maas, de Waal, de Merwede en de Lek. Printed by Isaak Tirion, Amsterdam. ↩︎

- Mathijs Boom (2023) extensively analyses Lulofs’ arguments and his biblical stance in his doctoral thesis., A diluvial land. Earth histories in the early modern Low Countries, 1550-1830. PhD-thesis Universiteit van Amsterdam. Note that Boom refers to the Rhine and Meuse branches and the coastal plain as a delta, consistent with late twentieth century usage. ↩︎

- Christiaan Brunings played a central role in the creation of Rijkswaterstaat, a national institution for water management. I checked “Verhandeling over de Snelheid van Stroomend Water, en de middelen, om dezelve op allerleïe diepten te bepaalen”, Verhandelingen Hollandse Maatschappij der Wetenschappen te Haarlem 26 (1789a): 1–233. Also see Kleinhans, M.G. (2023). Measuring and Manipulating the Rhine River Branches: Interactions of Theory and Embodied Understanding in Eighteenth Century River Hydraulics. Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, https://doi.org/10.1002/bewi.202300004. Note that I refer to the Rhine and Meuse branches as a delta, consistent with late twentieth century usage. ↩︎

- The entire history of the Pannerdensch Kanaal, opened in 1707 to restore the division of flow discharge over the Rhine branches, and its relation to the Rijkswaterstaat institution, indicates that the large-scale connections were not lost on experts and stakeholders in the seventeenth century either. van de Ven G. 1976. Aan de wieg van Rijkswaterstaat–wordingsgeschiedenis van het Pannerdens Kanaal (in Dutch). De Walburg Pers: Zutphen, The Netherlands. ↩︎

- van der Sijs, N., and Beelen, H. (2015). Onze Delta. Onze Taal, 1(27). See https://www.etymologie.nl/ and https://www.etymonline.com/word/delta#etymonline_v_5547. Note that the google ngrams viewer shows a rapid rise of usage around the 1953 floods. ↩︎

- Lyell, Charles (1830). Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation. London: J. Murray. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/33224/pg33224-images.html ↩︎

- Also see chapter 2 in Boom (2023) ↩︎

- The debate whether something is a delta or estuary is more than semantic: by consensus in different disciplines, both words come with different connotations and the choice for either depends mainly on which aspects, mechanisms and timescales are of interest. See de Haas et al. (2018) for one review. ↩︎

- Van der Sijs and Beelen (2015) ↩︎

- Marie-Louise ten Horn-van Nispen (2001). Johan van Veen. Tijdschrift voor Waterstaatsgeschiedenis 10, p.16-20. ↩︎

- Kamerstuk II, 1955-1956, 4167, nr. 1-3, Wet op de afsluiting van de zeearmen tussen de Westerschelde en de Rotterdamsche Waterweg en de versterking van de hoogwaterkering ter beveiliging van het land tegen stormvloeden (Deltawet); Koninklijke Boodschap; Ontwerp van wet; Memorie van Toelichting. https://repository.overheid.nl/frbr/sgd/19551956/0000278501/1/pdf/SGD_19551956_0002279.pdf ↩︎

- (1967, p. 3): the delta project. Published by the information department of the Ministry of Transport and Waterstaat in co-operation with the Delta Department of ‘Rijkswaterstaat’ and the Netherlands government information service. March 1967. A later version is nearly exactly the same: https://open.rijkswaterstaat.nl/publish/pages/158567/132843.pdf ↩︎

- van den Brink, M. (2021). Rijkswaterstaat: Guardian of the Dutch Delta. In: Boin, A., Fahy, L.A., ‘t Hart, P. (eds) Guardians of Public Value. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51701-4_10 ↩︎

- Testing this might be an interesting though slightly cynical citizen science experiment. Meanwhile, for private fun, enjoy https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=swamp, https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=mire and https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=bog. ↩︎