Historical research is something we would not have associated with a laboratory. Instead of the dusty smell of books in an archive, we were suddenly exposed to the sizzling of pans and the strong scent of wine and burned wood.

Still, this is where we found ourselves, as students of the Utrecht University History and Philosophy of Science course History of Knowledge, coordinated by dr. Carine van Rhijn, dr. David Baneke and dr. Daan Wegener. Guest lecturer dr. Thijs Hagendijk introduced us to historical research using experimental practices in the ArtLab. Thijs is an assistant professor of technical art history at Utrecht University and specialises in the history of practical knowledge. Prior to his workshop, we had exclusively studied texts as primary and secondary sources, relying on our imagination to make sense of recipes in, for example, the Picatrix, a treatise on astral magic. In Thijs’ workshop, we had the chance to actually experience the process of following 16th-century instructions.

During these two workshops, we followed an early-modern recipe for ink-making and explored the procedure of printing botanical illustrations. As our program coordinators helped us realise during the course, visual representations are essential for conveying knowledge. Therefore, developing a deeper understanding of the decisions relevant to their making is useful when studying the history of knowledge. The process of historical experimentation could help us question our primary sources in a different way than before. We were eager to find out.

Ink-making

To make the ink, we used a recipe from The Secrets of the Revered Maister Alexis of Piemont, published in 1595.1 We learned that this book was reprinted and copied often throughout the years and commonly used for making ink until the 18th century.

We began by trying to decipher the handwriting and meaning of the Old English words, which turned out to be more difficult than expected. Lacking familiarity with reading gothic letters, we mistakenly understood ‘stamped’ as ‘damped’. Luckily, we discussed our interpretations with our peers – otherwise, we might have added water to the recipe instead of simply crushing the ingredients! After agreeing upon the most likely transcription of the text, we rewrote it, in contemporary English., ‘Ye shall take good Galles, and breake them in three or faure perces’1 became ‘you shall take good gallnuts and break them in three or four pieces’. After we sorted out the steps required to implement the recipe, Thijs supplied us with the following ingredients: vitriol, gallnuts, white wine, Arabic gum and oil. At this point, we were ready to start our ink-making process.

New challenges then arose. For example, the quantities described were ambiguous (e.g. more than a hand width). Even when measurement units were explicitly mentioned, we wondered if their values had changed over time. Was a pound the same quantity in the 16th century as it is now? The recipe also contained guidance on adjusting the ink viscosity if needed, where the execution eventually relied on our subjective assessment of proper ink characteristics. Did the wine have the same consistency? Why not use water instead? What type of vitriol did they use? It was these practical struggles that made us realise how much tacit knowledge the text contained. This also led to a group discussion regarding what the author probably assumed to be general knowledge at the time. The whole process challenged our preconceived view of what practising history meant.

With the scents of warm wine and burning wood arising from our pans, this class reminded us more of cooking than the experience some of us have had in today’s scientific laboratories. The lab is a place that is associated with exact measurements and precision, where subjective assessments should be left “at home”. In contrast, cooking relies on personal taste and the adjustments of the recipe according to preference. It made the kitchen and the household, as a place for experimentation, much more tangible in our understanding.

Let us note that we are aware that the questions we have encountered can emerge without personal involvement in experimentation. However, we believe that by working with our hands, it did in a much more spontaneous and numerous ways.

Drawing, etching, printing

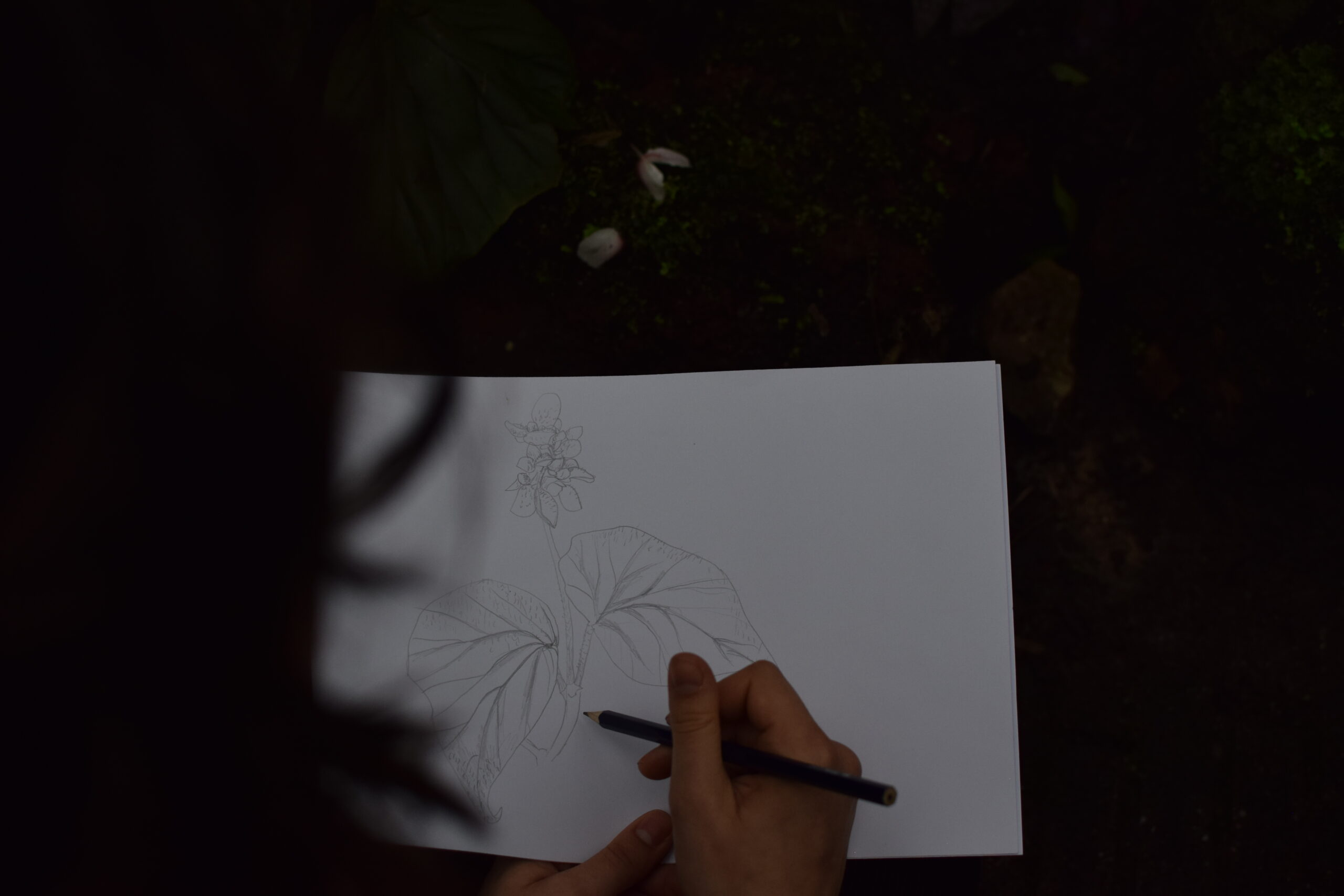

Our experience did not end with ink-making. The week after, we started our second project in the botanical gardens. Equipped with a pencil and a piece of paper, we were asked to draw a plant of our choice. Walking around the botanical gardens to find a suitable plant was as enjoyable as it was challenging. We felt like adventurers looking for the perfect plant for our project. Now confronted with another aim than we had during previous leisure visits, we looked differently at the plants. Did we want to pick a plant that was exceptionally pretty or one that was easy to draw?

After choosing one plant, we began the drawing process, which led to unexpected issues. The flowers or plants we decided to draw often did not fit on the paper, so we had to select the parts to include and, at the same time, which elements to exclude. This affected the drawing’s accuracy. The same scaling issue resurfaced when replicating the drawing on a smaller metal plate in a later step. Furthermore, the levels of detail chosen were very different depending on the person and the goal of their drawing. Some of us decided to present a pretty image of the plant, while others preferred to focus on its characteristics for better identification. The drawing process reminded us that, as history students, we need to understand the substantive impact that practical problems and decisions can have on the development and codification of knowledge. Not everything was intentional. In the analysis of a visual representation, it is often tempting to imagine that any divergence from the reality of the object is the author’s artistic will, but this experience showed us otherwise.

Back in the art laboratory, Thijs gave us careful instructions about the next steps. just like the historical actors, we relied on the knowledge of printing that was being explained and shown to us instead of following a written recipe, like with the ink making. By focussing only on written sources this verbal transfer of knowledge may be overlooked, so it was useful to get both experiences in the workshop. He handed each group a small zinc plate coated in a protective layer, easily scratched away with a needle. The exposed surfaces would hold the ink in the printing step, so scratched lines should equal printed lines, although this did not turn out well for every student. Indeed, one of us drew overly thin lines on the zinc plate. That led to issues in the later step where the ink needed to get into the grooves, and the most detailed part of the drawing, where the lines were the thinnest, stayed invisible. After putting the plates in the acid bath, they were cleaned with benzine, covered in an oil-based ink, and cleaned with paper scraps. We needed to moisten our paper before printing to make it more flexible, less prone to tearing, and more absorbent. The last steps entailed slightly drying the paper and positioning it on the inked plate. To press the paper, all groups used a bench-top etching press.

Just as for the ink-making, these steps required some experience. If, for example, the paper was not dry enough for printing, the ink would smudge. To get this right the first time was not easy. Once again, we faced difficulties with the skill and experience required to make a print, but Thijs helped and guided us through the process. The networks of sharing printing knowledge almost seemed invisible when looking at a botanical illustration. Yet, we can only assume that historical actors also needed guidance in learning how to print. Many choices about these representations lay in the hands of the printers and the artists. This draws attention to seeing collaborative efforts in fields of knowledge production instead of the more common individualistic approach of historians. During our experience of replicating the process, we faced a lot of these choices. For instance, how did the authors depict different stages of plant life? Did they rely on secondary material to avoid spreading out the drawing process more than necessary over time?

Conclusion

Rethinking the processes and experiences described in historical texts was valuable to understand better the considerations that historical actors must have had.

Firstly, getting our hands dirty, so to speak, was an insightful way to come up with questions about a historical process and its context. Following the ink recipe forced us to think about every detail of the process. In addition, during the printing process, we experienced difficulties that may have been encountered by printers who used that technique. It allowed us to engage with a different position, that of the practitioner, which inspired us to think from their point of view. Trying to recreate the whole multi-sensory experience unquestionably helped us to do so. We had to decide whether the pressing was sufficiently damp, which made the feel of the paper crucial. Secondly, more subjective choices attached to a process emerged. In our case, what parts of the plant did we want to include? Did we idealise the plant in our drawing or try to be as truthful to nature as possible? These questions might not arise from the study of a text alone. Thirdly, it is an efficient way to realise what was assumed to be common knowledge for the intended audience. In a purely literary study, it might be more difficult to think of all the information implicit in the text. During the reproduction, however, we were confronted with the missing pieces of information. For instance, when reading a text that mentions “oil”, we might not think twice about the reference. However, when we had to reproduce the recipe and list the ingredients, we thought about the characteristics of the oil. What kind of oil would have been used? In that way, we had to think more deeply about the historical context of a recipe.

Throughout the reproduction process, it was crucial to remain critical and be aware that we might have made unconscious assumptions. Hence, we realised that reproduction is not a one-to-one replication of what people used to do. During our experimental research, it can be easy to get carried away with speculation based on our subjective experiences of the reproduced procedure. These issues, however, are not unique to the experimental side of historical study.2

Although we should be cautious about making conclusions regarding historical hypotheses, we believe our time in the lab has given us valuable insights into ink-making and printing. We believe experimental methods were valuable additions to our history of knowledge program when applied in tandem with traditional literary research. The workshops were definitely exciting, and we would love opportunities to include this in our future research. Undoubtedly, there’s more to history than just books.

Acknowledgements

We thank dr. Carine van Rhijn, dr. Daan Wegener and dr. David Baneke for offering this course and dr. Thijs Hagendijk for organising the workshop at the ArtLab (https://artlab.sites.uu.nl). Furthermore, we thank our classmate Dimitris Manolarakis for taking the nice pictures that we use in this story.

Bibliography

- Alessio A. Ruscelli G. Ward W. Androse R. Short P. Wight T. & Thordarson Collection. (1595). The secrets of the reuerend maister alexis of piemont : containing excellent remedies against diuerse diseases wounds and other accidents with the maner to make distillations parfumes confitures dyings colours fusions and meltings : a worke well approued verie necessarie for euerie man (Newly corr. and amended and also somewhat inlarged in BSPS 2024 Annual Conferenceplaces which wanted the 1st). By Peter Short for Thomas Wight.

- Sibum, H. O. (2016). From the Library to the Laboratory and Back Again: Experiment as a Tool for Historians of Science. Ambix, 63(2), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00026980.2016.1213009