“The heart hangs out of the neonate’s body, as if it beat too harshly for too long and pulsated its way forward. It makes me wonder about whether this child was loved by someone wholeheartedly, or if it made someone’s heart beat extremely fast for other reasons than affection, like fear or fascination.”

(My personal thought process when viewing a displayed fetus with ectopia cordis, currently exhibited at museum Vrolik)

Have you ever thought about when your story started? Was it when your parents were born? Or when they got to know each other? Was it when they found out your mother was pregnant with you, or when she felt you kicking for the first time? Or was it when you were born and took your first breath? These questions are always individually answered and are already hard enough to answer about your own story, let alone somebody else’s. The same can be said for historical actors. In historical research, we often know very little about these very human and emotional experiences surrounding the birth of a child, the start of life itself, and even the end of one’s life: when does your story end? Does it end when you let out your last breath? When your funeral has passed? When your loved ones have worked through their grief, or when they too pass on, and your memory passes with them? Historians are constantly trying to make sense of these moments in historical actors’ lives: How did they experience being a child? Or giving birth to a child? How did people cope with death? Or the nearing of death? While birth and death separately capture the historian’s attention, a lot less attention has been given to when the birth and death of an historical actor coincide. When life ends as it starts, namely at birth. Often lacking in written source materials, historians have needed to get creative on writing the history of stillbirth.

In this paper I would like to suggest that you can learn about the historical conceptions of this coinciding of life and death, and the historically fluid concept of ‘the fetus’, by studying anatomical collections. They contain tangible remnants of the past: from the eighteenth century onwards, the ‘start of life’ was eternalized in anatomical preparations of the fetal body. Dutch universities collected and preserved a wide range of anatomical specimens to teach medical students about embryological development, ranging between embryos of a few days old to infants of a few months old. These fetal remains now reside in multiple anatomical museums in the Netherlands, where they provoke a wide range of emotions and thoughts to the museum visitor. The values and meanings of these remains have transformed and evolved over time, with museums needing to be cognizant and respectful of this evolution when they consort with human remains. Anatomical museums see themselves morally obligated, or even forced to adapt to a care-approach when it comes to their collections of human material: care for both its visitors and for the human remains themselves.

When walking through these anatomical collections, it is often difficult to see the preparations as “human”, not in a mere medical sense of the word, but as parts of social beings, as individuals with their own stories. It is difficult to identify oneself with the story behind the flesh, behind the objects. Often enough the absence of a narrative to which one can feel connected renounces a fetus to a mere anatomical object. As historians it can be most fruitful to look for these narratives, as they hold a power: each object has a story to tell and a trajectory to trace. When it comes to a human fetus, and its path to the museum, its trajectory is shaped by objectification, historicization, and museumification. In my PhD research, I want to trace the trajectories and stories of the fetuses that currently reside at Museum Vrolik, the anatomical museum of the University of Amsterdam (now housed in the Amsterdam University Medical Center). The collection at the Museum Vrolik has historical value and continues to be of great medical value, even more so nowadays, since a lot of the congenital defects present in the collection rarely exist in the present day – or are rarely carried to term. Tracing the provenance of their preparation helps us to understand why they were collected, and how we should approach them today. What is to come is one such example: the story of a fetal body of a child with Ectopia Cordis.

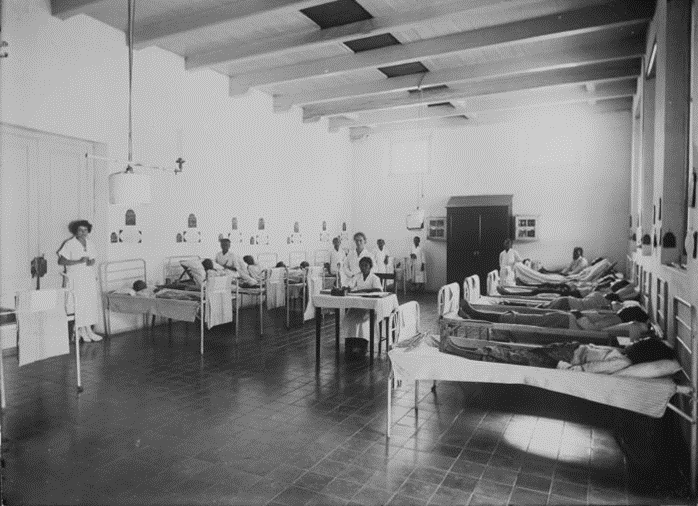

The hospital

The story starts, like so many other birth stories, at a hospital. Sometime in the autumn of 1926 a woman gave birth to a child at the Central Civil Hospital in Semarang, Java. The child had a congenital defect called Ectopia Cordis, a condition where the heart is located partially or totally outside the thorax. Despite this condition, the child lived for a total of three days before it succumbed to the symptoms of tetanus. Losing a child at three days old is something no one is prepared for, so we can only imagine the feelings that joined this passing. However, to this day, this remains imagining only, for other than a comment of a doctor claiming the parents were “of pure Javanese descent”, we know nothing of the baby’s parents, nor their feelings on the lost infant.1 When one loses a child and its physical story comes to an end, its story often continues through the thoughts and hearts of its loved ones, on a spiritual and emotional level. While we cannot be certain of how – and if – its emotional story continued, its physical story did.

The boat

And it went like so: the fetus was preserved for medical research and education at the hospital. The child was put into a glass jar where it was preserved in a liquid that allows for human tissue to withstand the test of time. One can wonder if the story of the human child ends here, and the story of an object just started. As the child is put into the jar, it converges into one object. Thus, a shift of substantiality took place from a deceased child to an educational tool which was then – by the request of doctor Lodewijk Bolk, anatomist and professor in Amsterdam – shipped to the Netherlands to be further researched. At the time, Bolk was also responsible for Museum Vrolik, the anatomical collection of the University of Amsterdam. This collection originated from the private anatomical collection of Gerard and Willem Vrolik, to which Bolk had added his own specimens between 1900 and 1930. So it happened that after a long delay, because of misunderstandings about when the shipment would take place and difficulties about the property rights, the fetus arrived in Amsterdam, canned in an aluminum container. From there it was likely preserved in formaline (a mixture of formaldehyde, water, and methanol) and it took its place among the other specimens of the Vrolik collection.

The museum

The fetus would never again leave Amsterdam, although it did move around within it, but always as part of the collection. Somewhere along the way, the meaning of its story changed. What used to be an individual child became an example of a disease that served a medical purpose only: to educate future doctors and to be kept as an exemplar of the unique congenital condition that it is. However, as time further progressed, and its story became history, another meaning and value was added on. The fetus became an historical object, and because of its hundred years of preservation, it gained historical value. When looking at this fetus and other preserved preparations, they allow us to gaze at past worlds in tangible ways. Their materiality and presence in our current world gives us unique insights into the ways of the past. As a result of this, the fetus is released from its mere medical frame, to be seen not only as an historical object, but personified as an historical actor once more.

Even though this object gained historic value, to say it is purely historical would be false, as it transcends the distinction between history and present-day. This object has a unique material composition. It consists of materials made by humans (the glass and conservation fluid) and human material (the fetus). This is of course a simplification of the matter, since the fetus was in fact also made by humans. The object, in its current material composition residing at the museum, consists of more recent and more historic materials. Whereas the human material, as well as the label (which reads: “1927 Ectopia Cordis (lived for three days) (Javanese)”), originated from the 1920s, the surrounding glass container and the conservation fluid have changed over time. In 2007, as part of a great restoration project that took place at the museum, a new glass jar was used, and the conservation fluid was changed.

A palimpsest

As the year 1984 (that George Orwell imagined) arrived, the anatomical collection moved to its current residence, at the UMC location in Amsterdam. It was Orwell who wrote in his classic dystopian novel 1984 that “all history was a palimpsest, scraped clean and re-inscribed exactly as often as was necessary”.2 The same could be said for objects from the past. As an item moves over time and space, different layers of value and meaning are added to it, or are replaced whilst the materiality changes with it. As the subject transcends into an object; as the medical object enhances into an historical one; and as the historical object transcends into an amalgam of history and present, the fetus remains. Next time you visit an anatomical collection, remember that these fetal remains tell a story, and that we can only guess what matters, values, meanings, and decisions lay in store for the future history of the boy whose life continued after death. But for now, it remains at the museum, still provoking a wide range of emotions to the museum visitors, still forcing ourselves to rethink and re-interpret our past, while trying to make sense of our own temporariness.

- Brief van E.J. Bok aan Lodewijk Bolk, over transport pasgeboren kind met Ectopia Cordis. 21 oktober 1924, collectie Museum Vrolik. ↩︎

- Orwell, G. (2021). Nineteen Eighty-Four, Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1949) chapter 4. ↩︎

Further reading

Museum Vrolik. https://www.museumvrolik.nl/en/.

Morgan, L. (2009). Icons of Life: A Cultural History of Human Embryos. Verenigd Koninkrijk: University of California Press.

Wellcome Collection. “Care of Human Remains Policy,” August 23, 2023. https://wellcomecollection.org/pages/WyjY_SgAACoALCmH.