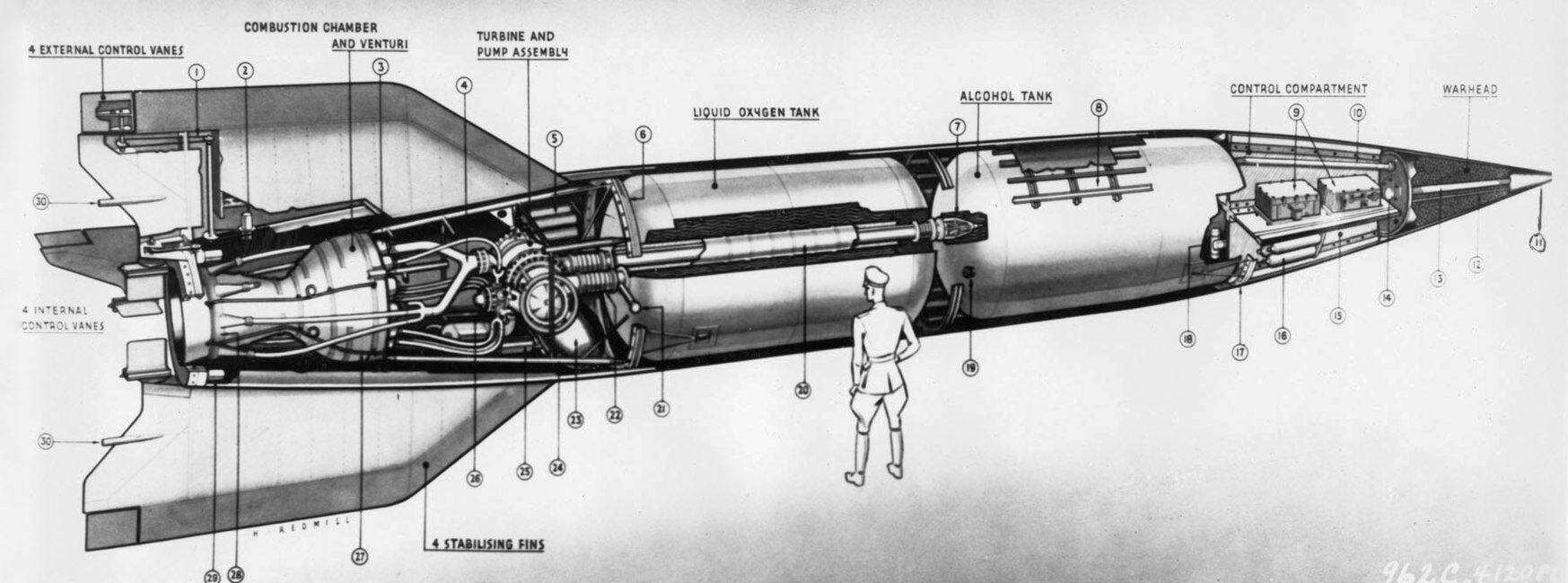

This year’s wars and the role of technology in them give us good reason to reflect on the trope of “wonder weapons.” Several recent articles talk about Russia’s use of drones and glide bombs in Ukraine in terms of wonder weapons, referring specifically to weapons used by the Nazis.1 The phrase has been used systematically as a way to describe Hitler’s pursuit of particular high technologies: weapons that would change the course of the war. The term frequently appears in scholarly literature, although authors disagree about exactly which weapons are subsumed by the category.2 The V1, V2, V3 missiles, nerve gas, and rocket planes are frequently described as “wonder weapons.”3 To this list, recent work adds submarines, the Me 210 airplane, and Germany’s Panther and Tiger tanks.4 The jet plane and the German atomic bomb have also been pronounced “wonder weapons,” although the latter was never realized.5

Historians state that the phrase “wonder weapon” came from Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry, implying that the term (with all its defeatist connotations – consider the idea that only a wonder could save your war) accurately reflected the governments’ way of thinking about technology.6 Yet there is no evidence of it in Nazi propaganda.7 Centralized National Socialist propaganda used the adjectives “new,” “miracle,” “secret” or “revenge” but never “wonder weapon” itself. Individuals like Stephen Breyer, who worked in a German shipyard during the war, later remembered hearing the word in propaganda during the war. This suggests either that the word was in circulation during the war or that post-war accounts connecting the term to the Third Reich have been very powerful in shaping memories of the war.8 The appearance of the specific phrase in Anne Frank’s diary in June 1944 (in reference to the V2) also suggests that the term was at least known, even if it did not appear widely.9

So why does this linguistic confusion matter? For three reasons. Firstly, it is frequently used by historians as a lens to understand Nazi technology, and has misled them – as discussed below — because it is not historically accurate. Secondly, it has had repercussions, particularly in the public sphere, where support for weapons programs often hinges on their relationship to justice. Lastly, it reveals a Cold War understanding of technology that characterises writing about Third Reich technology.

In order to understand how the Nazis viewed technology generally (and as a proxy, how the Allies and other contemporaries viewed technology), it is necessary to think outside the loaded term “wonder weapons”. The term has come to dominate the view of National Socialist weapons technology among historians. Yet there appears to be no empirical support that the National Socialist leadership held this particular view. The absence of the term from German propaganda, as I noted previously, suggests that the Nazis did not see technology in this way (as a decisive factor, able to bring a turning point in a war widely viewed as lost).10 This is not to say that the term did not circulate – Anne Frank’s diary suggests it did – but that it was not the dominant way that Germans thought about their own technology.

If one looks at German technological development projects through the lens of “wonder weapons,” one gets a rather different picture than if we proceed without it. Historians have accepted the idea that the National Socialist government was actively pursuing a policy of producing “wonder weapons.”11 This idea has occluded the real goals of National Socialist weapons development by suggesting that the government emphasised high-quality weapons. Today, however, it is well established that Albert Speer, one of Hitler’s closest confidants and Minister of Armaments in the Third Reich, in his efforts to increase weapons output, frequently produced technically outdated types.12 My research on the jet engine in Britain, Germany and the United States has shown that viewing such technology as a “wonder weapon” makes it impossible to grasp the real meaning of the jet engine for the National Socialist government. Rather than being an advanced weapon pursued for martial superiority, Germany’s jet engines must be understood as substitute (and inferior) piston-engines, cheaper to make than existing aero-engines.13 Because the engine’s particular qualities were successfully made to fit the distinctive needs of Nazi Germany’s war economy, the new technology was adopted by the Luftwaffe despite a multitude of risks.14 Understanding the jet as a “wonder weapon” puts understanding of the regime’s technology out of reach, placing yet another area of government policy behind the heading of ideology.

Looking beyond Nazi propaganda, there is measly evidence of the use of the term “wonder weapon” in wider culture. Indeed, its use seems to rise after rather than during the war.

The above graphs are based on books. Newspapers show something similar.15 The use of the term comes around World War two, and increases afterwards, earlier in English than in German. Although the term “wonder weapon” does not show great use, the idea of a powerful weapon is hardly new.

Lore suggests that older, powerful weapons were linked to an idea of justice. Because they carried with them the power to change the course of human history, they were generally given by a god to a human carrying out their work. The latter point was ensured in various ways. Consider Excalibur, for example, a famous weapon stuck in a stone (the sword was admittedly not created by a god, but by another mysterious, mythical being). Getting the sword out of the stone in order to use it is an excellent example of a (magical) test to ensure that the bearer was worthy of the weapon – in this case to ensure the bearer’s lineage. This notion that justice was associated with using a weapon and that the creator of the weapon could ensure the user had the correct motives to act – was influential in lore until the development of decisive technology in the Second World War proved it to be wrong.

The coincidence of high technology and evil in the second world war (indeed, technology was early on identified by the public as simultaneously the most modern and most evil aspect of the Third Reich), helped to destroy the association of powerful weapons with justice in the West.16 After World War II, we see the rise of the mad genius in the cultural sphere. If we think about James Bond, for example, the mad genius controls weapons so powerful that our hero must act. Or consider Lex Luthor’s bid for power – requiring a powerful weapon – in Superman in 1971 (see Figure 3. below). In this case, the powerful weapons are no longer associated with a just cause. Instead, the threat of their use and images of the destruction that they can cause inspires the hero to act. This is illustrative of the dissociation of genius and right in popular culture.

The last dimension of the term that historians and the public need to be aware of is: who benefits from promoting a vision of weapons as a dangerous threat? Someone selling new weapons systems (or atomic weapons) might well support an interpretation of history that proves the decisive nature of weapons. Lacking the assurance that weapons will be used for a just cause, super weapons are a threat that can only be responded to by creating weapons even more terrible. People selling protection, like Reagan’s “Star Wars” scheme, would similarly need to talk-up the capabilities of enemy weapons: a threat that needs to be dealt with.17 Governments take both sides: in the Cold War, they needed to justify their expenditure on both weapons and public safety.

We see the term used globally in the decades after the war to paint technology in a very particular way, valued apart from its use. The most well-known, post-war users of the term are important figures from the Third Reich like Albert Speer and Walter Dornberger, the administrative leader of the V2 programme. Although both men suggested after the war that the phrase had been used in National Socialist propaganda to mislead Germans into believing that victory was still possible through technology, the term actually more strongly appears in connection with post-war politics.18 For example, Speer’s defence during his Nuremberg trial depended on his characterization of himself as a technician and “wonder weapons” as ludicrous; both rhetorical moves that absolve human responsibility by treating technology as the most decisive factor in human events.19

Crucial here is that the division of the engineer from the technology’s ultimate use (and thus might from right) appeared in other places in the same time period. After the war, while various court cases were going forward against highly placed Nazis, the Allies were all busily trying to steal German technologies and technologists – increasingly so if only to deny them to the Soviets. The final value of taking German technology to Allied nations was unknown at the end of the war, so enormous investments were made into exploiting German technology on the chance that gaining German technologists or technologies would be valuable. Because of this, actors taking Nazi technology naturally described these programs as very important and successful – a characterization that has also informed the historiography.20

The story of exploitation also made very convenient the acceptance of Speer’s assertions that the Nazi engineers were not generally tainted by their Nazi past when recruiting talented engineers like Wernher von Braun, leader of the V2 program, who later served as an important foundation of the American space program.21 Instead, they were ideologically malleable engineers who could be split from their ideologies and given a new one. Selling Nazi technology as wonderous neatly explained why non-Nazi states had to use it, and why they had to harbour German technologists, regardless of the ideology question. The theft of German technological talent was part of the reparations which the Allies felt was due to them, so justifications were loudly shared. This practically important rhetoric (that German technology was hugely important and exploitation programs were a big success) undoubtedly influenced historians too.

The idea of “wonder weapons” has moved from infrequent, general use, to being used almost exclusively in reference to the Third Reich’s weapons (and other nations viewed as aggressors, but only if the Third Reich is also discussed). Far from a creation of wartime propaganda, the term seems in fact to have been shaped by Cold War views of technology, when the notion of a super powerful weapon was one that the general public, cowering under the threat of atomic destruction and viewing images of the moon landing, believed in. It is worth spending time to look at the rhetoric of wonder weapons, because, however distant from our experience it may seem, it still today brings with it assumptions about the decisiveness of technology that condition our own responses to it. Today, the term “weapons of mass destruction” evokes the same fear and powerlessness that “wonder weapons” did historically.

- Raphel S. Cohen, “’Wonder Weapons’ will not win Russia’s war”, RAND Commentary, 2022, 10 November, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2022/11/wonder-weapons-will-not-win.html. Michel Peck “Glide Bombs: The Russian Wonder Weapon?”, Centre for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), 2024, 9 April, https://cepa.org/article/glide-bombs-the-russian-wonder-weapon/. ↩︎

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich at War 1939-1945 (London: Allen Lane, 2008), 754; Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (London: Penguin, 2007), 613; Mark Walker, German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 1939-1949 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 88; Ralf Schabel, Die Illusion Der Wunderwaffen: die Rolle Der Düsenflugzeuge und Flugabwehrraketen in der Rüstungspolitik des Dritten Reiches (München: Oldenbourg, 1994); Karl-Heinz Ludwig, Technik und Ingenieure im Dritten Reich. (Konigstein, Düsseldorf: Athenaum, Droste, 1979), 432 and 487. ↩︎

- Evans, Third Reich at War, 670-1. ↩︎

- Tooze, Wages of Destruction, 612-3. ↩︎

- Walker, German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 44 and 78. ↩︎

- Mark Walker, ‘The mobilization of science and science based technology during the Second World War’, in A. Maas and H. Hooijmaijers (eds.) Scientific Research in World War II: What Scientists Did in the War (London and New York 2009), 13–30; Daniel Uziel, The Propaganda Warriors: the Wehrmacht and the Consolidation of the German Home Front (Oxford and New York: P. Lang, 2008), 319; Roderick Stackelberg, The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany (New York and Abingdon: Routledge, 2007), 307; Benjamin King and Timothy Kutta, Impact: The History of Germany’s V-Weapons in World War II (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 2003), 326; Schabel, Illusion Der Wunderwaffen, 19; Walker, German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 91; Ludwig, Technik und Ingenieure im Dritten Reich, 447. ↩︎

- Goebbels archive (Militairarchiv, Freiburg, Germany). See also his publications: Joseph Goebbels, “Ein Volk in Verteidigungsstelle,” Das Reich, February 11, 1945. He hints that Germany is making a super weapon that will turn the tide of war but does not use the phrase “wonder weapon”. In Joseph Goebbels, “Unsere Chance”, Das Reich, February 18, 1945, he no longer hints at a weapon but suggests that German determination can still win the war. Also, in his cross-examination at Nuremberg, Albrecht Speer claims that both Hitler and Goebbels claimed the idea was not from their propaganda. Albert Speer, ‘Speer Cross-Examination’, 1946, accessed January 3, 2012, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/nuremberg/speer.html. ↩︎

- Breyer, Siegfried. “Wunderwaffe” Elektro-Uboot Typ XXI. Marine-Arsenal Sonderheft 13 (1996): 36. ↩︎

- “Dinsdag, 27 Juni 1944…Wel is de Wuwa (wonderwapen) in volle actie, maar wat beduidt zo’n sisser anders dan wat schade in Engeland en volle kranten bij de moffen? [The Wuwa (wonder weapon) is in full action, but what does another V2 mean other than some damage in England and full newspapers among the Krauts?]” Quote from Anne Frank, Het Achterhuis. (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Contact, 1947). ↩︎

- Ludwig, Technik und Ingenieure im Dritten Reich, 445; Schabel, Illusion Der Wunderwaffen, 19; Evans, Third Reich at War, 657-60. The key characteristics of ‘wonder weapons’ are hard to identify. The category represents the end point of the regime’s discourse of ‘qualitative superiority’, in which Germany was meant to combat and overcome the enemy’s clear quantitative superiority through better weapons. See Walker, German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 90; Ludwig, Technik und Ingenieure im Dritten Reich, 439. Yet through the V-weapons, including the most well-known, the V2, “wonder weapon?” has also been connected with revenge as an alternative to military victory. See Evans, Third Reich at War, 658. Evans also brings attention to another feature, which he ascribes particularly to the regime’s ‘wonder weapons’: economic irrationality. ↩︎

- Schabel, Illusion Der Wunderwaffen, 257; Ulrich Albrecht, ‘Military Technology and National Socialist Ideology’ in Science, Technology and National Socialism, ed. Monika Renneberg and Mark Walker (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Andreas Heinemann-Grüder, ‘“Keinerlei Untergang”: German Armaments Engineers During the Second World War and in the Service of the Victorious Powers’, in ed. Renneberg and Walker, Science, Technology and National Socialism; Overy, Richard J. Goering: the ‘Iron Man’ (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), 197; Walker, German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 1992. ↩︎

- Tooze, Wages of Destruction. ↩︎

- Hermione Giffard, “Engines of Desperation: Jet Engines, Production and New Weapons in the Third Reich,” Journal of Contemporary History 48, no.4 (2013): 821-844. The article was awarded the George Mosse prize for best article by a previously unpublished author in April 2014. ↩︎

- Hermione Giffard, “The Development and Production of Turbojet Aero-Engines in Britain, Germany and the United States, 1936-1945” (PhD diss. Imperial College, London, 2011); Bernhard Rieger, Technology and the Culture of Modernity in Britain and Germany 1890–1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 41. ↩︎

- Chronicling America, Delpher, Deutsches Zeitungportal (https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/search/newspaper?query=Wunderwaffe). ↩︎

- Chronicling America, Delpher, Deutsches Zeitungportal (https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/search/newspaper?query=Wunderwaffe). ↩︎

- Peter J. Westwick, “From the Club of Rome to Star Wars: The Era of Limits, Space Colonization and the Origins of SDI” in Limiting Outer Space: Astroculture After Apollo, ed. Alexander Geppert (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 283-302. ↩︎

- Albert Speer, ‘Speer Cross-Examination’ (1946), accessed January 3, 2012, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/nuremberg/speer.html; Walter Dornberger, V2 – Der Schuss ins Weltall: Geschichte einer Grossen Erfindung (Esslingen: Bechtle, 1952), 114-6. ↩︎

- Albert Speer, “Two Hundred and Sixteenth Day Saturday, 31 August 1946” in Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Volume 22 : Two Hundred and Twelfth Day – Two Hundred and Eighteenth Day, accessed 6 June 2024, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/08-31-46.asp.

↩︎ - Hermione Giffard, “Review: Exploiting Nazi Science and Technology and the History of Technology Transfer” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 50, no. 1/2 (2020): 199–208. The books reviewed include: Charlie Hall, British Exploitation of German Science and Technology, 1943–1949 (London and New York: Routledge, 2019); Martijn Van Calmthout and Michiel Horn, Sam Goudsmit and the Hunt for Hitler’s Atom Bomb (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2018); Douglas O’Regan, Taking Nazi Technology: Allied Exploitation of German Science after the Second World War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019); Brian E. Crim, Our Germans: Project Paperclip and the National Security State (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018). ↩︎

- Von Braun is the primary example of this. See Neufeld’s recent biography: Michael Neufeld, Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War (United Kingdom: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2017) ↩︎