This is the third in our series of interviews with current historians and philosophers of science. In these interviews, our guests are asked to reflect on the current status of the field, how we might be able to contribute to contemporary debates, what their own research interests are, and how these interests inform their worldview. While enjoying a cup of rooibos tea, professor Rina Knoeff speaks about her work with Ruben Verwaal, currently curator at Erasmus MC and her PhD student from 2013 to 2018. They focus on the history of medicine, gendered healthcare, and the value of premodern history in reflecting on urgent health challenges today.

Rina Knoeff (RK): I am Aletta Jacobs Chair of Health and Humanities at the University of Groningen. Many people confuse the chair with the Aletta Jacobs School of Public Health, but they are independent. The chair was created in 2021 by the University Board to increase the number of female professors.1 At that time I was already active in the Aletta Jacobs School for Public Health, an interdisciplinary venture of the RUG, the UMCG and the Northern HBO’s. I had also founded the Groningen Centre for Health and Humanities. The full professorship is not only a continuation of my work, but also – and this is a great thing! – an expansion of the total number of Chairs in the fields of history of medicine and health humanities in the Netherlands.

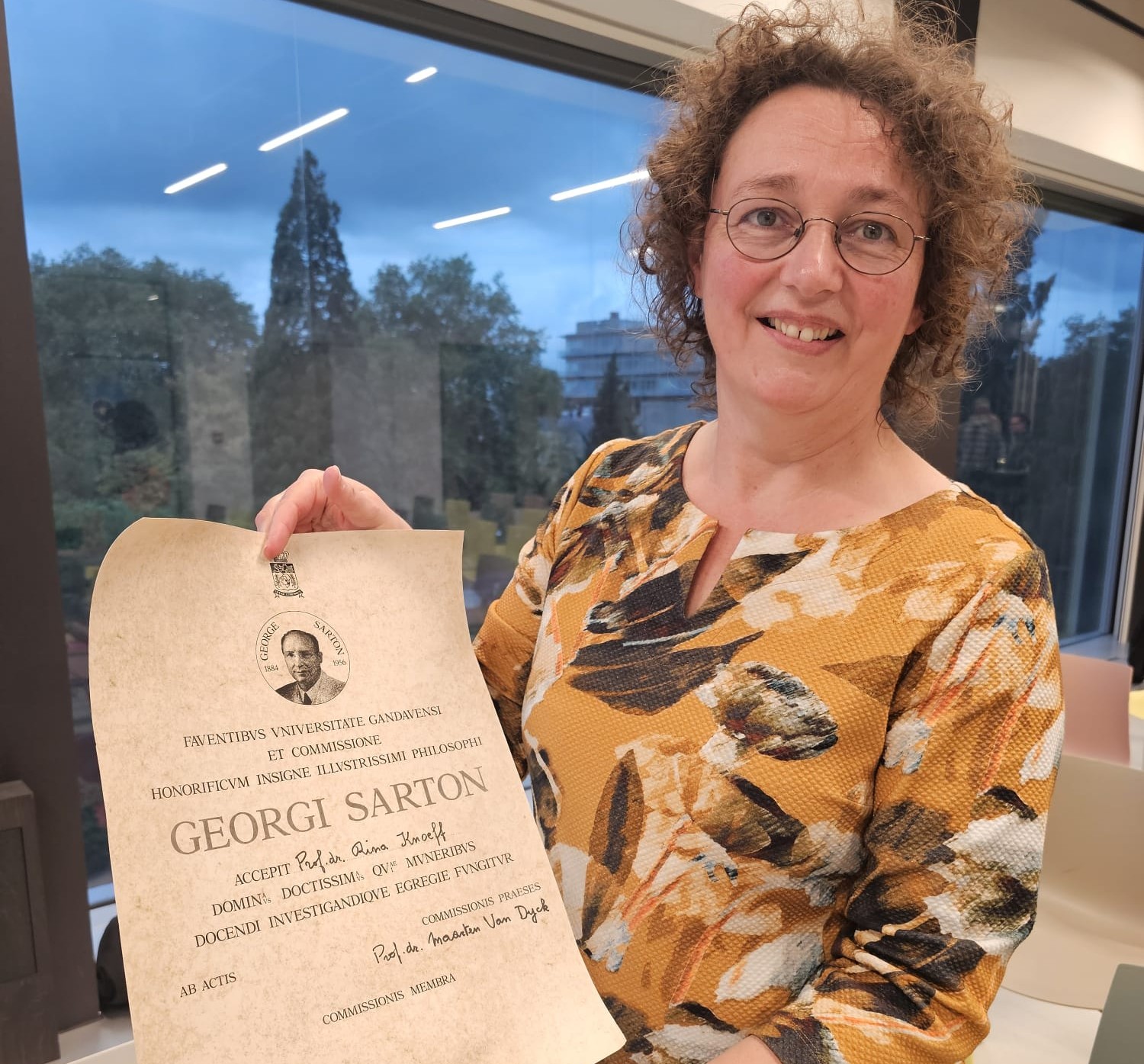

Ruben Verwaal (RV): And you’ve recently been awarded a Sarton medal at Ghent University, named after one of the founding fathers of the history of science, George Sarton (1884–1956).

RK: Yes, not only a medal, but I am also this year’s Sarton Chair for History of Science at Ghent University.2 The Chair is a symbolic Chair, and I have just given my inaugural lecture. I feel very honoured and pleased as the prize is of course also an important encouragement for the field of health humanities and the cooperation between Dutch and Flemish Universities.

Sarton Medal, 2024. Photo: Rina Knoeff.

RV: What was the oration about?

RK: The lecture was titled ‘Medicine and the Female Body: A Historical Consultation’. I asked how a more positive approach to the female body from early modern times can inspire healthcare today. A recurring theme in explaining the origins of today’s gender health gap, is the alleged tradition of patriarchal and misogynist attitudes toward women. But we seem to have forgotten that the discipline of medicine also contains a premodern tradition that valued and cared for the female body as the most natural site of perfect health. Paradoxically, though, premodern medicine also viewed the female body as the seat of the most horrible diseases, which led to gender specific treatments.

Paradoxes like this have been central to my research: I’ve always been fascinated with things that cannot easily be explained. Medical history is packed with crazy stories. I don’t push those aside as unrealistic, nor do I try to think what it could have been, or what kind of modern disease people might have suffered from. I take these stories seriously and consider them in their own time, trying to understand what they are about. It is always the case that these stories are attempts at rational explanations, stemming from a completely different, yet rational worldview, which I find fascinating.

RV: We hear a lot about the importance of public engagement. What would you say is the role of HPS and history of medicine in informing today’s science, medicine, and society?

RK: Well, generating research impact is not a one-way street, with academics doing research, after which they tell society about it. I want to tackle urgent issues head-on, which means that you have to engage with today’s health challenges right from the start. It is fascinating to see that the problems that people used to wrestle with in the past are largely the problems we are facing today. Then the question is: how can the past function as a mirror, helping us think about solutions today? I’m not saying we should uncritically adopt past solutions, nor am I saying that history repeats itself, and I’m not cherry-picking either. But I do think history functions like a mirror, because we actually do the same thing: we also try to rationalise weird things and bizarre phenomena, and give them a place in today’s world.

RV: And is being an early modernist an added value in reflecting about today’s urgent issues?

RK: Yes. People may feel alienated, but early modern science and medicine alienates even more. Some things are very similar, such as the phenomena of epidemics or people’s feelings of pain, loss and practices of mourning. But modern medicine is mainly based on developments dating back to the 19th century and to a certain extent recognisable. Yet, premodern medicine and health are fundamentally different, which forces us to look at it in a cultural context. This move – to look at medicine and health as a cultural and societal issue – makes us aware that today’s medicine and health are likewise embedded in culture and society. So that very alienation helps with holding up that mirror to understand what we are dealing with beyond a purely medical context and approach, and to get to the heart of the problem.

RV: So could we say that a common thread in your work is reflecting on contemporary events and issues from a long-term, early modern perspective?

RK: True, it is today, but it has not always been the case, because my work on Herman Boerhaave was predominantly hard-core history of science.3 The turning point for me was curating the exhibition Gelukkig gezond! Histories of Health Ageing at the University Museum in Groningen in 2017.

It was halfway my NWO VIDI research project, which was rooted in my Boerhaave PhD research, so purely history of science and medicine. But ‘healthy ageing’ had become a central research theme of the Groningen University. And I kept thinking that healthy ageing was central in history of medicine too and that ‘we in the humanities should participate in the research line’ (with the hope of also participating in research funding). It was all very novel and exciting: we went to the UMCG (University Medical Centre Groningen), contributed to nephrological research, and discussed the theme with policymakers of the city of Groningen.

All this resulted in the Gelukkig gezond! exhibition, which was admittedly somewhat basic – more a book on the wall with relatively few objects – but the idea was good, it attracted many visitors, and the accompanying catalogue was a great success.4 As I was invited everywhere to talk about it, I suddenly realised that our knowledge is very important to a lot of people outside our field and outside academia.

Poster for Gelukkig Gezond! exhibition, 2017. Photo: Rina Knoeff.

RV: What changes to our field stand out to you as particularly salient? What are the new trends in HPS and medical humanities?

RK: Social relevance has become increasingly important. For early modernists this poses as a challenge, but applies just as strongly. During the Covid pandemic, I was sometimes called by journalists and they always asked me to speak in ‘nuanced one-liners’ – which I then thought long and hard about, because it is quite a challenge. It is a skill you have to learn, because that way you can show why history is important, what it can contribute in terms of thinking about solutions.

At the same time, I don’t think we should forget fundamental research and we are in danger of losing sight of that now. That is why I’m very happy that the Centre for Health and Humanities is not in a medical faculty, but in the Faculty of Arts. That way we are not a handmaiden to medical research, but we have the liberty to set up our own research lines and use the academic methodologies of history writing. This does not mean that I here argue for a strict separation between historians and medics, or that I am saying that historians of medicine are better than medical historians. On the contrary, I strongly believe that in being separate from the medical faculty, we can research and work together in a better and non-hierarchical way.

RV: What are the greatest barriers for the field to make progress and how do we overcome them?

RK: The biggest threat to our field, I think, is political. We are all facing the devastating consequences of upcoming cuts in higher education and research. Even more dangerous are the increasingly dominant idea that science is ‘just another opinion’, and the contradictory and naïve idea that technology will solve all our troubles. We already see that it is dividing academia, with the technical sciences and the HBO’s (Applied Higher Education) increasingly arguing that their disciplines are more important than the ‘thinking disciplines’ at the faculties of humanities and social sciences. The threat of serious cuts in humanities funding is very real – and very depressing, as much of the excellent work we have done over the last decades will undoubtedly suffer. What we can – and must – do is double our efforts in showing what the humanities can contribute; how important we are as conversation partners in solving today’s challenges.

RV: Let’s say we jump to 2044 and you’re about to give your farewell oration. Looking back at the last 20 years, what directions would you hope to see the field of HPS to have taken?

RK: I very much hope that by then we will also have some kind of tradition that is more continental Europe and a little less Anglo-Saxon. We are now very much looking towards the Anglo-Saxon tradition as our great example – and rightly so, because their work is excellent as a result of much better funding structures. Yet, I think it is about time to find our own identity, rooted in continental European sources and stories, and even share them in our native tongues besides English. This is not another call to hide behind the dikes – but it is important for the diversity of our field to hear and compare more and different perspectives, questions, and source materials.

In addition, I hope there will be more recognition within the university for popular science work. On the one hand, for funding purposes we are all asked to have an impact plan, but popular science publications, which are at least as difficult to write and for which you need to do the same research, still do not count academically.

RV: As a final question, can you give a literature suggestion for our Shells & Pebbles readers?

RK: A book I recently read and very much enjoyed, is Jenni Nuttal’s Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women’s Words (2023). It is such a great little book, about the language we use today and in the past. Already in the introduction, we learn that the very first time the word ‘mann’ or ‘mon’ was used in Old English, it referred to a woman with menstrual problems. Nuttal calls it ‘rather marvellous’ how the word ‘Mann’ or ‘mon’ stands for ‘mankind’, which ‘was once not quite as default male as it sounds to modern ears’. Being an early modernist, I likewise come across alien words in Dutch that nevertheless hit the nail on the head (for example ‘lip-pleyster’ referring to a kiss). It makes me think that it would be simply delightful to have a similar cultural history of Dutch medical language.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Any external links have been added by the editor and are not direct references of the interviewee.

- You can read Rina’s inaugural lecture here: Old as Methuselah? Supercentenarians, Narrative Wisdom and the Importance of History for Health. Inaugural Lectures. Groningen: University of Groningen Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.21827/64edb67ea5dec. ↩︎

- Click here for an overview of past Sarton chair holders: https://www.sartonchair.ugent.be/en/pastchairholders (accessed 26 October 2024). ↩︎

- Knoeff, Rina. Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738): Calvinist Chemist and Physician. History of Science and Scholarship in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: Edita, 2002. ↩︎

- Knoeff, Rina, ed. Gelukkig Gezond! Histories of Healthy Ageing. Groningen: Barkhuis, 2017. Translated into Japanese as リナ·ノエフ, ed. 老いと健康の文化史:西洋式養生訓のあゆみ [Cultural History of Old Age and Health: The History of Western-style yōsō kyōgen]. 東京: 原書房, 2021. ↩︎