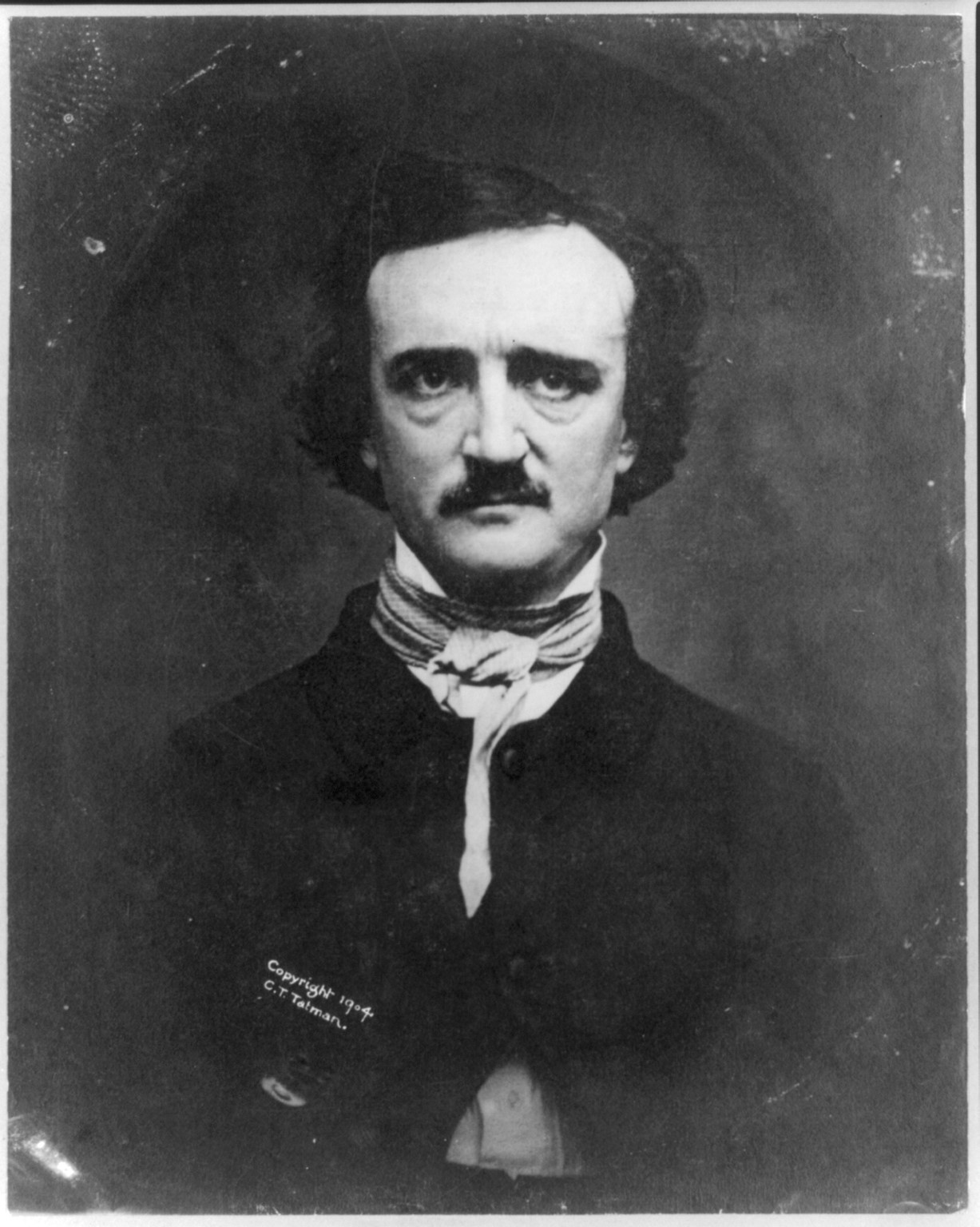

Edgar Allan Poe lived from 1809 to 1849 and made a narrow living with his writing career in the eastern cities of the United States of America. Most who know of Edgar Allan Poe know of his eerie poetry and gothic short stories, macabre and mysterious: “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Raven,” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” to name a few. Poe, however, had a larger literary career: as an editor, a literary critic, and a scientific writer. As one biographer wrote, Poe could be considered “the strangest and saddest figure in American literature.”1 And quite strangely indeed, “Poe’s greatest hit,” as Stephen Jay Gould titled his 1995 essay on the topic, was not gothic poetry, but a textbook on the science of shells (conchology) and mollusks (malacology), titled The Conchologist’s First Book: A System of Testaceous Malacology, Arranged Expressly for the Use of Schools, in Which the Animals, According To Cuvier, Are Given with the Shells, a Great Number of New Species Added, and the Whole Brought Up, as Accurately As Possible, to the Present Condition of the Science (1839).2 Of the various books and pamphlets Poe published under his name, The Conchologist’s First Book alone sold well enough to merit reprinting in a second (1840) and eventually a third edition (1845) while he was still alive.3 The Conchologist’s First Book, in all its editions, was created by plagiarizing, and accusations of plagiarism followed Poe in life and in death. I wish to explore the exact nature of the plagiarism involved because I believe that understanding Poe’s plagiarism will lead to a more nuanced understanding of Poe, the complexities of public science in the early United States, and plagiarism more generally.

Context and Contemporaries

To begin with the subject of the book itself, conchology was the highly popular study of mollusks’ shells, and malacology the significantly less popular study of the animals within. Conchology’s popularity corresponded directly to the popularity of shell collecting among Europeans and European-descended colonial populations between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Shell collecting was a natural history mania during this period for a handful of reasons: the easy preservation of shells compared to animal taxidermy, the rarity and beauty of specific shells from distant locations, as well as pre-existing associations between shells and Christian pilgrimage or the mathematical perfection of some shells themselves.4 Conchology also offered business opportunities for the enterprising, both through sourcing rare or beautiful shells and verifying the legitimacy of shells’ identities for wealthy collectors. An individual selling their conchological expertise in the form of a guide and lecture could, with some luck, make a fair bit of money, leading to a glut of conchological manuals on the market. For the most enterprising, however, the work to reward ratio of a conchological book could be improved significantly by taking advantage of the absence of copyright enforcement for books in the United States during this period and simply plagiarizing the available conchological manuals and natural histories. Poe was one such enterprising writer.

The aspiring American conchological author (or plagiarist) in 1839 would be entering a hierarchical scientific situation that corresponded roughly to nationality. At the summit of the scientific hierarchy were the recently-deceased French biologists Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, the creator of the first scientific theory of biological evolution, and Baron Georges Cuvier, the first scientist to successfully argue that species could go extinct. Lamarck and Cuvier had written sweeping natural histories and thus had covered both conchological and malacological information in their extensive careers. A half-step below Cuvier and Lamarck stood Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville, a French zoologist who had published scientific volumes on both shells and their animal inhabitants, lavishly illustrated and extremely detailed due to the extensive resources de Blainville had access to in the French Academy of Sciences.5 A further step below the French Academy in prestige were the British conchologists: Thomas Brown, a natural history writer and military captain who would later become curator of the Manchester Museum, and John Mawe, a well-regarded mineralogist and sea captain. Both British authors created conchological manuals for a lay audience focusing on the resource (the shells) rather than the animals as a whole.6

Moving to the United States and going down another step in prestige, there were conchologists and shell collectors who worked in the publishing industry and influenced the creation of published works on their preferred subject. For example, John Warren was a bookseller and shell collector in Boston who combined a few different authors’ works into a conchological manual published under his name, while Isaac Lea was a conchologist and publisher in Philadelphia who likely influenced Poe’s book and the circumstances of its creation.7 Below all of these strata were the people actually writing conchological (or malacological) manuals in the United States: marginal figures to science who had the ability to write, some knowledge on the topic (or the ability to accumulate knowledge quickly), and a need for money.8 This category included Edgar Allan Poe, who had gone to university and made his living–narrowly–on his writing, but also included university students, professors, teachers, and public lecturers.9

The Real Plagiarists of Philadelphia

One of the scientific lecturers in the United States of the late 1830s was a man named Thomas Wyatt. Wyatt and Poe worked together on at least two books between about 1838 and 1845 in Philadelphia, but very little else about Wyatt himself or Wyatt and Poe’s collaboration during this period is known with any certainty.10 Poe claimed that Wyatt was a professor, and Wyatt’s obituary in the New York Herald claimed he was a professor at William and Mary College in Virginia, but Wyatt’s professorship cannot be verified as the records of William and Mary were mostly destroyed in 1859.11 Wyatt’s literary career offers a window into the issues identifying authorship or expertise in this period.

In 1846, Wyatt claimed to have written four books, all textbooks about natural history: of these four, two were published with Wyatt’s name on them, one was published with Poe’s name on it, and there is no evidence of the last book’s existence.12[12] After 1846, Wyatt published at least another five books under his name, all on political, religious, and military history.13 Poe does appear to have been involved in some of the natural history books Wyatt later claimed, and Poe and Wyatt may have worked on books published under other names as well, as Wyatt claimed to have hired Poe for multiple projects.14 However, Wyatt only revealed any information about Wyatt and Poe’s collaboration after Poe had already died, and only one letter between the two is known. Furthermore, due to a literary feud that metastasized into a vendetta, Poe’s first biographer forged and altered letters from Poe and possibly destroyed documents entirely in order to harm Poe’s posthumous reputation.15 Between the absence and destruction of evidence, the details of Poe and Wyatt’s collaboration will likely forever remain mysterious.

Nevertheless, we can attempt to reconstruct the most likely scenario from the information available. What seems to have happened was as follows: Wyatt published, or was part of publishing, a book of conchology under his name in 1838. A Manual of Conchology, According to the System Laid Down by Lamarck, with the Late Improvements By de Blainville was published in New York City for, at the time, the high price of $8.16 Wyatt’s Manual sold poorly, but the New York publishers refused to create a cheaper version, so Wyatt took his book to Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, Wyatt and Poe appear to have worked on at least two books together that were both published in 1839: one, published under Wyatt’s name, was a general natural history text, and the other, published under Poe’s name, was The Conchologist’s First Book.17 As discussed above, it is not clear who did what work on what book, and it is entirely plausible that all of Wyatt’s natural history works involved some amount of collaboration with Poe and perhaps others.18 To avoid too much repetition, Wyatt shall be referred to as the author of the Manual of Conchology and Poe will be referred to as the author of The Conchologist’s First Book, but it is unlikely that these authorship assignments are correct. The book published under Poe’s name sold well–likely helped by the fact that Wyatt, as discussed and evidenced by Gould, was probably selling and using The Conchologist’s First Book at his public lectures.19

In 1846, Poe was accused of plagiarism in a Philadelphia newspaper, defending himself against the charge in a letter to an acquaintance in 1847 (Poe died in 1849).20 The original charges of plagiarism against Poe were, depending on the source, that Poe had copied the book of one of the British shell-collectors in its entirety, or perhaps even that Poe had been paid $50 for his name without contributing anything else to the conchological book with his name on it.21 In his 1995 essay, Gould assumes that Wyatt is writing with conchological knowledge and argues that Poe made important edits to the later, cheaper, Philadelphia book that ensured its success.22 Plagiarism, perhaps, but not fully without merit as a text at the time. These stories about Poe’s plagiarism are, as best as I can determine, unverified or inaccurate. Poe’s book and the British book alleged to be Poe’s source are not identical in several key aspects, such as overall structure and the species descriptions, and the plagiarism is simply not that straightforward. That Poe would sell his name for a small sum fits slightly too cleanly with the posthumous slander surrounding Poe after his death, which is when that story emerged.23 The story might be true but is just as likely to be an exaggeration or fiction. On the other hand, considering Gould’s account, Wyatt does not appear to have been an expert in anything beyond writing public education books, so it is unlikely that Poe merely used Wyatt’s expertise and a British book on the subject. Wyatt’s and Poe’s plagiarisms are, in fact, highly complex, but there is a basic pattern to both books.

How To Commit International Plagiarism

Poe and Wyatt took sentences, passages, and images directly from other works without crediting or mentioning those works–or doing so incompletely. To understand why and how they plagiarized, we should go back to the scientific hierarchy I discussed above and start ascending it. Firstly, we can begin with the local experts. Both Poe’s and Wyatt’s books use the organization and accepted species lists from another American conchological book, which may have reflected the state of science in America as American scientists saw it.24 Consistency with ‘accepted science’ in the time and place of writing would help legitimize Poe’s and Wyatt’s books to an American audience. Additionally, both Poe and Wyatt mention a Philadelphia publisher and conchologist who likely contributed the species that Poe’s book identifies as being local species–information unlikely to be emphasized by European sources but which would be valuable to American readers.25

Figure 1: Thomas Brown, The Conchologist’s Text-book, 1833, Plate 11 (left); Edgar Allan Poe, The Conchologist’s First Book, 1839, Plate 12 (right). The red letters to the upper left of the matching shells denote the copied shells. The last four shells from Poe’s page of images shown here were copied from Brown’s Plate 10, labeled there as 1, 2, 8, and 24. Image edited by the author.

Secondly, we should turn to the British shell collectors. While Wyatt claims to have had his images drawn from his own physical collection of shells, this is an evidently false claim.26 (Poe makes no particular claims). Poe’s book rearranges the images of shells from one British conchological book (Fig. 1), and Wyatt’s book takes about half its images from another one (Fig. 2). At the center of a sprawling maritime empire actively collecting treasures from its colonies, the British authors would simply have had far better access to shells from across the globe than two part-time American textbook writers. Additionally, both Poe and Wyatt take substantial pieces of text describing the locations of shells and, in Wyatt’s case, the appearances of specific species’ shells, from the British authors. It is also worth noting that, unlike the dry scientific manuals of either the American or French writers, the British manuals were intended for lay audiences. Thomas Brown’s book, in particular, seems to have been copied for its educational value: Brown’s glossary of terms appears in both Poe’s and Wyatt’s texts, and Brown’s description of the different parts of shells with the appropriately labeled diagrams appears in Poe’s text (Fig. 5).

Figure 2: John Mawe, The Linnæan System of Conchology, 1823, Plate 3 (left); Thomas Wyatt, A Manual of Conchology, 1838, Plate 3 (right). The handwritten notes are from an unknown owner of Wyatt’s book. Image edited by the author.

Finally, we ascend to the rarefied air of the French Academy of Sciences. The prestige of Lamarck and Cuvier–and the lesser prestige of de Blainville–meant that the French figures are claimed to be the sources for Wyatt’s and Poe’s books. Beyond prestige, there is another reason for Wyatt and Poe to freely admit the influence of French sources: it’s not copying, it’s translation. Wyatt’s Manual does take from de Blainville, as the title of Wyatt’s book implies, but both more and less than Wyatt admits. More than Wyatt admits, because the images that Wyatt did not take from his British source are copies of de Blainville’s images of shells, which is not ‘translation’ (Fig. 3). Less than Wyatt admits, because Wyatt does take some text from de Blainville but not as much as Wyatt claims. More of the text in any given species description in Wyatt’s Manual is from the British authors rather than de Blainville, likely because the British authors speak to the interests of lay audiences–the appearances of different shells–more than de Blainville does. Despite claiming to be based on Cuvier, Poe’s book also uses de Blainville, drawing almost entirely on it for its species descriptions of both shell and animal. I would venture that Poe’s use of Cuvier here is to try and muddy the waters and prevent the New York publishers of Wyatt’s manual from getting suspicious, as Lamarck–named in Wyatt’s text–and Cuvier–named in Poe’s–were famously rival figures.

Figure 3: H. M. Ducrotay de Blainville, Manuel de Malacologie et de conchyliologie, vol. 2, 1827, Plate 63 (left); Thomas Wyatt, A Manual of Conchology, 1838, Plate 14 (right). Image edited by the author.

Wyatt’s and Poe’s choices were calculated. The images in both books were copied from artists in colonial centers with far-flung empires that could accumulate these natural jewels (as they were seen at the time) from the far ends of trade networks. American scientific institutions had the advantage of local information, but the general scientific expertise of European institutions held sway at this time–in no small part because of the accumulation of specimens that empire facilitated in both France and Britain. While biologists existed outside of France, Cuvier and Lamarck further benefited from the centralization of the French Academy of Sciences to popularize their biological theories across and beyond France, partially leading to their–and de Blainville’s–elevated status.27 Finally, Wyatt and Poe were not being paid a rate commensurate to even the American experts for their work. And for Poe the literary critic and general writer, developing a deep understanding of the nuances of shell structure would likely have been impossible and impractical. Wyatt and Poe were not experts and could not become experts, so they plagiarized from those who were.

Plagiarism, Defined and Applied

Up to this point I have been using the term “plagiarism” in an unexamined way, assuming the reader will have an idea of what that entails. While plagiarism is frequently reasoned about in terms of theft, I will use a different definition.28 Charles Rosen, a philosopher writing on music, describes a gradation of influence from visible (plagiarism) to invisible (transformed) in a final work:

“With plagiarism, we have two works in which some part of both is identical, a part too large for the identity to be fortuitous. … As we move away from such simple situations–that is, as the later artist transforms the borrowed material into something more his own–this relationship is put into question. The critic must still claim an identity between something in the earlier work and the material of the new work. But what gives him the right to maintain this identity except a resemblance which diminishes as the transformation is more thorough?”29

To put Rosen’s question another way: is a collage, or an artistic work that cuts images and text from magazines or other print media and recombines them into a new arrangement, plagiarism–or, still worse, theft? Collages rely on a multitude of unacknowledged graphic designers, photographers, and artists for their base materials, but it would seem strange to claim that the final result was plagiarism. Theft seems even further from what children (and many others) create with scissors, glue, magazines, construction paper, and free time. Rosen’s definition of plagiarism as the far end of a spectrum of creative transformation also leaves room for collaborative or facilitated creation and expression.30

So, what gives me the right to maintain that Wyatt and Poe were plagiarists rather than textual collage artists? If it is a lack of citation which indicts the plagiarist, then plagiarism occurred. For one thing, Poe later claimed that he “wrote the Preface and Introduction, and translated from Cuvier the accounts of the animals etc…”31 Poe’s text, however, is a copy of de Blainville, not Cuvier.32 In addition, there is a copy of the first edition of Poe’s Conchologist’s First Book believed to have belonged to Poe himself, in which there are a number of handwritten corrections and notes.33 While some of those corrections made it into the second and third edition, the written note “[Thanks] [a]lso to Mr. T. Brown upon whose excellent[sic] book he has very largely drawn” did not appear in any later version.34 If this is indeed Poe’s own copy, this note would imply Poe was aware of and at least privately acknowledged his behavior as plagiaristic. In Wyatt’s book, the majority of the text was taken from unacknowledged British authors, so he was also plagiaristic by a lack of citation.

Generally, the belief about plagiarism is that credit–intangible or not–has been taken from the people who “deserve” to have it.35 However, as previously noted, collage artists rarely credit their sources either. To take another tack, plagiarism is also a sort of thoughtlessness: namely, the belief on the part of the creator of the final work that they have no thoughts worth sharing.36 A collage is a new creation that reflects the creator. The sources are transformed by their juxtaposition with the other pieces of the collage; though the pieces are not original, the creation as a whole is. In theory, there could be a work made only of quotations that nonetheless is a new, original creation: the interaction of words previously isolated from each other now read together, on the same pages. In theory, Poe and Wyatt could have created academic summaries, taking the first-hand accounts of others and rearranging them in a novel way or for a novel purpose, or synthesizing the different sources into a new, condensed description.

Poe and Wyatt did not create a juxtaposition, summary, or synthesis. Wyatt’s and Poe’s texts are both far to the plagiaristic side of the spectrum of transformation and show markers of thoughtless copying. At the level of individual sentences and individual images, Wyatt’s text shows a level of integration: some of his pages of images are combinatorial between his French and British sources (Fig. 4) and his species descriptions are a combination of the translated scientific French text of de Blainville with the more layperson-oriented descriptions of shell appearance and shape from the British authors. Structurally, however, Wyatt’s manual is identical to one of the earlier American manuals–more detailed, but not particularly novel. Furthermore, Wyatt verges into repetitiveness relatively frequently, keeping pieces of text from multiple sources that provide identical or nearly identical information.37 Methodologically, this repetitiveness suggests either that Wyatt is unsure of the topic to the point that he would rather keep both descriptions than synthesize them, or that Wyatt was mechanically copying from his sources and did not note the repetitiveness enough to correct it. The information was not transformed or synthesized but simply collected into a pre-existing shape, so I would argue that Wyatt’s text is best understood as a plagiaristic text.

Figure 4: Thomas Wyatt, A Manual of Conchology, 1838, Plate 6 (top left); John Mawe, The Linnæan System of Conchology, 1823, Plate 8 (top center); H. M. Ducrotay de Blainville, Manuel de Malacologie et de conchyliologie, vol. 2, 1827, Plate 70 (top right); Plate 73 (bottom left); Plate 78 (bottom center); Plate 79 (bottom right). The red letters signal which shells Wyatt took from Mawe and de Blainville. Image edited by the author.

Poe’s text is more and less straightforwardly plagiaristic. One of the British authors, Thomas Brown, who Poe privately but not publicly acknowledged as a central source for his text, is the source for multiple sections of Poe’s textbook. Brown’s description of the shells and Brown’s glossary are reproduced without any alteration (Fig. 5), and Brown’s images of shells are somewhat rearranged to fit in the American structure but otherwise simply copied over (Fig. 1). On the other hand, Poe departs from the structure of his English-language sources by, importantly, including information on the animals as well as the shells taken from the French de Blainville. By including the scientific description of the animals inside rather than the physical product and monetary good of the shell alone, Poe’s text gains significant scientific credibility and informative power within the space of English-language conchological books. For shell collectors, many of the shells would still have their animal inhabitants and being able to distinguish the animals from each other could assist in identification. For students, or the scientifically minded layperson, including the animals would have lent Poe’s text a scientific rigorousness absent from other English conchological manuals of the time.

Figure 5: Thomas Brown, The Conchologist’s Text-book, 1833, Plate 1 (left); Edgar Allan Poe, The Conchologist’s First Book, 1839, Plate 1 (right). Note the identical lettering labeling each shell–this is because Brown’s text describing each figure was also copied verbatim into Poe’s book. Image edited by the author.

That being said, Poe’s text contains a consistent error that argues for this text being plagiaristic rather than synthetic. In the genus descriptions, which make up the bulk of the text, Poe’s text first uses the translated shell and animal descriptions from de Blainville’s French text before appending information from the British Thomas Brown on the location that this genus can be found. This appended location information is uniformly true only of a single species in the genus, specifically the last species Thomas Brown provides in his book for that genus, and is incorrect to describe the genus as a whole.38 In other words, Poe (or the writer responsible for this part of Poe’s text) spliced out the context from Brown which would make the location information useful and accurate, either because of a lack of knowledge to notice the error or a lack of inclination to work more carefully. Poe’s text is more novel when taken as a whole, but even a bit of a closer look reveals the patchwork and thoughtless reuse of other work without alteration, and so I would argue that this text, too, is plagiaristic.

Conclusions

There is a very small amount of surviving evidence from Poe’s publicly published works and letters that speak to how Poe (and perhaps Wyatt) thought of their work on the natural history books from this period. In 1847, Poe corresponded with an acquaintance about the previously mentioned accusation of plagiarism made the previous year in the Philadelphia Saturday Evening Post.39 In that letter, Poe gives an account of the creation of The Conchologist’s First Book:

“I wrote it, in conjunction with Professor Thomas Wyatt, and Professor McMurtie of Pha – my name being put to the work, as best known and most likely to aid its circulation. I wrote the Preface and Introduction, and translated from Cuvier, the accounts of the animals etc. All school-books are necessarily made in a similar way.”40

Poe is not telling the truth here. As I previously argued, the book with his name on it draws on de Blainville and not Cuvier. The naming of another figure, McMurtie, also reinforces the insubstantiality of authorship during this period.41 It is the last sentence, however, that I wish to focus on. That sentence echoes another that Poe wrote. Earlier, I mentioned that Wyatt claimed to have authored four natural history books: two with his name on them, one with Poe’s name on it, and one that has since vanished without a trace. Poe reviewed one of the books Wyatt’s name appeared on–a book that Poe also plausibly contributed to, meaning that Poe might be speaking from direct experience.42 In that review of another half-translated natural history work from French, Poe blithely mentioned that when adapting a French author for American schools, “some little latitude was of course admissible and unavoidable.”43 To that quote, we might append the end of the above quote: “All school-books are necessarily made in a similar way.”44

The bringing of science to the public has, historically, rarely been an activity for scientists. Far more frequently, the pen writing a scientific publication meant for the public (including the public attending school) is or was a scientist-in-training, a teacher, or a writer who delved into science. In general, these people are (or were) writing from a combination of economic necessity and legitimate interest, with the balance of economic to intellectual factors varying based on the individual. It is my hypothesis that, in a social system, the extent to which economic factors push people into writing science for the public will be positively correlated with science for the public being under-researched and produced using plagiaristic methods. This hypothesis will be more salient for disciplines in which there is currently a strong public interest, as the potential economic returns and available sources to borrow from will be highest for those subjects. Conchology was such a subject in the era of Wyatt’s and Poe’s collaboration, but fashions change. Additionally, if the financial position of the writer is insecure, as was true of science lecturers and writers in the first half of the nineteenth century, tendencies towards plagiarism and thoughtlessness will accelerate, because the marginal figures creating public science will have less economic ability to choose otherwise. “Some little latitude was of course admissible and unavoidable–all school-books are necessarily made in a similar way.” These words are self-exculpatory on Poe’s part, justifying the choices already made as both unremarkable and necessary.

It is also worth casting a critical eye toward the hierarchy of science described earlier in combination with the “plagiarism as theft” metaphor I briefly mentioned. Publicizers of science–textbook writers, science journalists, etc.–receive substantially less credit than those who create the science itself. When plagiarism is considered theft because an idea put to paper can be rightfully owned, the minimal allocation of credit makes a certain amount of sense. Publicizers of science cannot own the material they communicate–at best, they “lease” it from scientists to communicate it onward. Their work is therefore less inherently valuable, and their “credit” is thereby diminished. Why are “all school-books necessarily made in a similar way”? The credit can only trickle downward from its origin at the top, and so, scientific publications for the public must name the scientists producing the base material (the better known, the better), the base material cannot appear to be too altered from its original state, and, finally, it is in the writer’s interest to take minimal ownership over their work so that their work is seen as scientifically legitimate. There is a distinct tension between the idea that a publicizer of science is a conduit that should only facilitate the communication of science to the public and the reality that scientific findings must be synthesized and reprocessed for the public to understand them accurately. The plagiarism-as-theft metaphor applied to scientific work seems to encourage thoughtlessness on the part of the scientific communicator, for any thought they add to the work is not a scientific thought and can only adulterate the scientific content. In other words, to return to one of the sources on plagiarism mentioned above, scientific communicators should be thoughtless, because in this dynamic, the communicators themselves have no thoughts worth sharing.45 Oddly, it is the idea that plagiarism could be stealing an object of value that makes plagiarism a logical output of attempting to communicate science–for it is the object of value, the science, that must be duplicated and must be preserved (but one can never admit it was taken, for that would be theft).

I do not wish to suggest that most or all science communicators are plagiaristic, nor that they believe in general that they have no thoughts worth sharing. Nonetheless, the train of thought detailed above suggests, for example, that students could benefit from being told that their writing assignments are opportunities to practice taking ownership of their ideas when writing summaries or analyses.46 The implications of these ways of thinking about plagiarism should also lead us to reevaluate these ideas in general. Earlier, I provided the counterexample of a collage as a creation that, if intellectual property can be stolen, should count as theft and therefore plagiarism. There are a number of possible reasons that the images that go into a collage might not feel like they are owned by someone else. The collage artist generally has to buy a copy of the work or be given it for free, which may transfer ownership in some socially mediated way, or perhaps the media conglomerate or advertising agency behind many of the images is difficult to assign credit to and so collages do not seem like theft.47 I wish to point to another possibility, one reinforced in a number of the sources I read discussing plagiarism: that while collaborative or mediated creation seems like the exception rather than the rule, it is in fact what underlies all creation. Plagiarism, then, may be better understood as a failure to ethically collaborate with one’s influences.

Plagiarism is, fundamentally, the belief that the writer has nothing to say combined with the necessity of saying something. Thinking about that dynamic through the language of theft is not particularly enlightening, because it does not get at why people copy the work of others without attribution. Credit, I would argue, should still be offered, but this is in order to allow others to understand one’s reasoning more deeply or to take inspiration directly from the same sources. For those who make public science, asserting the originality of transformation and juxtaposition may help them break away from a relationship where they begin in debt to scientists. As all creators do, they rely on those who made before and still create something original and worthwhile.

- Jeffrey Meyers, Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy, First Cooper Square Press (New York): 1992, p. xi. ↩︎

- Stephen Jay Gould, “Poe’s Greatest Hit,” Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History, Harmony Books (New York): 1995, p. 173-186; Edgar Allan Poe, The Conchologist’s First Book: A System of Testaceous Malacology, Arranged Expressly for the Use of Schools, in Which the Animals, According to Cuvier, Are Given with the Shells, a Great Number of New Species Added, and the Whole Brought Up, as Accurately As Possible, to the Present Condition of the Science, 1st ed., Haswell, Barrington, and Haswell (Philadelphia): 1839. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/54559. While The Conchologist’s First Book is sometimes characterized as Poe’s only foray into scientific writing, this is debatable: first, his works of fiction did often rely on scientific knowledge, including “The Gold-Bug” (about cryptography) and The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (about Antarctica); second, he also wrote and published Eureka: A Prose Poem, which was a book of cosmology written from intuition alone, dedicated to Alexander von Humboldt. ↩︎

- The main difference between the first versus the second and third editions is that the text and species lists of the later editions were based on Lamarck. ↩︎

- Barbara T. Gates, “Introduction: Why Victorian Natural History?” Victorian Literature and Culture 35, no. 2 (2007): 539-549, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40347173; Richard Conniff, “Mad About Seashells,” Smithsonian Magazine (August 2009), www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/mad-about-seashells-34378984/. ↩︎

- H. M. Ducrotay De Blainville, Manuel de Malacologie et de conchyliologie, vol. 1, F. G. Levrault (Paris): 1825. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/43891; H. M. Ducrotay De Blainville, Manuel de Malacologie et de conchyliologie, vol. 2, Planches [Plates], F. G. Levrault (Paris): 1827. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/45815. ↩︎

- Thomas Brown, The Conchologist’s Text-Book, Arranging the Arrangements of Lamarck and Linnæus, with a Glossary of Technical Terms, Archibald Fullarton & Co. (Glasgow): 1833, p. 157-158. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/54058; John Mawe, The Linnæan System of Conchology, Describing the Orders, Genera, and Species of Shells, Arranged Into Divisions and Families: With a View to Facilitate the Student’s Attainment of the Science. Self-published (London): 1823, p. 191-192. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/54279. ↩︎

- John Warren, The Conchologist, Russell, Odiorne & Metcalf (Boston): 1834. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/86753; Richard I. Johnson, “On the Authorship of the First American Conchological Manual, John Warren’s, ‘The Conchologist’”, Occasional Papers on Mollusks 6, no. 7 (30 August 1999): p. The Department of Mollusks, Harvard University. Accessed atwww.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/54136726; Isaac Lea was a prolific conchologist who was, at the time, the vice president of the American Philosophical Society. George W. Tryon, Jr., “Tryon, George W., Jr. “A Sketch of the History of Conchology in the United States”. The American Journal of Science and Arts, Series 2, Vol. 33: 1862, ed. Silliman, Silliman, and Dana. Hayes (New Haven): 1862, p. 165-166. Both Poe and Poe’s co-plagiarist Thomas Wyatt mention Lea as important contributors to their work in the introductions of their works. ↩︎

- Please note that this description of a scientific hierarchy is based on a rough sketch of biology in the early nineteenth century that I have made in order to help readers not get lost in a sea of names and book titles. My brief justification for these tiers is this: firstly, France (and its empire) was extremely scientifically centralized at the time from the late Bourbon monarchs’ and Napoleon’s efforts, and, partially on the back of those centralized resources, Cuvier and Lamarck remain important biological names to this day; secondly, Britain (and its empire) focused scientifically on geology (e.g. Lyell) and chemistry (e.g. Davy) rather than biology/natural history (until Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace in 1859); and finally, the United States was a colonial outpost barely done asserting its own existence (American Revolutionary War and War of 1812) and generally took cultural inspiration from France and Britain. From the perspective of the early United States, France and Britain would have been the only sources worth drawing from, and in the history of biology, the center of biological research and theorizing in the early nineteenth century lies squarely in France rather than Britain. ↩︎

- For example, Warren’s book The Conchologist was, according to Richard I. Johnson’s research, mostly the work of two university students. Johnson, “On the Authorship of the First American Conchological Manual,” Occasional Papers on Mollusks. ↩︎

- Joseph J. Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree: A New Poe Letter”, American Literature 42, no. 4 (January 1971), p. 468-477. Accessed at www.jstor.org/stable/2924719. ↩︎

- Letter from Poe to George Eveleth, February 16, 1847, The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, vol. 17, ed. James A. Harrison, J.D. Morris and Co. (New York): 1902, pg. 278. Accessed at babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015000547771. “Marriages and Deaths: Wyatt”, New York Herald, February 13, 1873, p. 8, column 6. Accessed at the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn83030313/1873-02-13/ed-1/. In Wyatt’s books, he is “Thomas Wyatt, A. M.” (Artium Magister) but not a professor. Complicating matters, William and Mary College’s Wren Building, and with it many of the college’s records, burned in 1859 and again in 1862. “Fires”, William and Mary Libraries, Special Collections Research Center, https://scrc-kb.libraries.wm.edu/fires. Accessed January 3, 2025. If Wyatt was a professor at William and Mary College, no record survives. ↩︎

- Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree”, American Literature. The two books published under Wyatt’s name were A Manual of Conchology (ft. 18) and a general natural history treatise called A Synopsis of Natural History. Thomas Wyatt, A Synopsis of Natural History: Embracing the Natural History of Animals with Human and General Animal Physiology, Botany, Vegetable Physiology and Geology, Translated from the Latest French Edition of C. Lemmonnier with additions from the works of Cuvier, Dumaril, Lacepede, Etc. And Arranged As A Text Book for Schools, Wardle (Philadelphia): 1839. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/137933. Wyatt later claimed The Conchologist’s First Book, which was published under Poe’s name, and also claimed on the title page of many of his known books to be the author of an “Elements of Botany.” There is no record of that book being published under Wyatt’s name, and I am unaware of any book with that title that Wyatt is believed to have contributed to. ↩︎

- The US Library of Congress catalogue contains a total of 17 books from the nineteenth century listing Thomas Wyatt as a contributor, of which 7 refer to the correct Thomas Wyatt. Two books listing Wyatt are the previously mentioned natural history books, A Manual of Conchology and A Synopsis of Natural History. The remaining five have the following titles, shortened and in chronological order: History of the Kings of France (1846), Memoirs of the Generals, Commodores, and other Commanders… of the Wars of the Revolution and 1812 (1848), The Sacred Tableaux, Or Remarkable Incidents in the Old and New Testaments (1848), Gems from the Sacred Mine: Or, Holy Thoughts Upon Sacred Subjects By Clergymen (1851), and Beauties of Sacred Literature (1852). Catalogue accessed at www.loc.gov/books, filtered to only books or printed material, contributor Thomas Wyatt, and dates between 1800-1899. ↩︎

- Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree”, American Literature, p. 472. ↩︎

- Rufus Wilmot Griswold’s forgeries and the unknowable destroyed letters are, in American literary circles, notorious for both their pettiness and for the damage they have done to scholarship on Poe. An incomplete list of Griswold’s forgeries is in J. W. Ostrom, B. R. Pollin, and J. A. Savoye, “Appendix C,” The Collected Letters of Edgar Allan Poe — Vol. II: 1846-1849 (2008), pp. 899-932. See also Arthur Hobson Quinn, “Chapter 20,” Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (1941), pp. 642-695. ↩︎

- Thomas Wyatt, A Manual of Conchology, According to the System Laid Down by Lamarck, With The Late Improvements by de Blainville, Exemplified and Arranged for the Use of Students. Harper and Brothers (New York): 1838. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/41355. ↩︎

- Poe, The Conchologist’s First Book, 1839. ↩︎

- In addition to Wyatt claiming authorship of The Conchologist’s First Book, which he did on the title page of History of the Kings of France, Poe publicly claimed authorship of the Synopsis of Natural History, both doing so in 1845. Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree”, American Literature, p. 472. ↩︎

- Gould, “Poe’s Greatest Hit,” Dinosaur in a Haystack. Gould follows the history of a specific copy of The Conchologist’s First Book that he got and concludes that the handwritten notes were likely done at lectures given by Wyatt. ↩︎

- Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree”, American Literature, p. 471; Letter from Poe to George Eveleth, February 16, 1847, The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, vol. 17. ↩︎

- Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree”, American Literature, p. 471, and p. 470, footnote 2. ↩︎

- Gould, “Poe’s Greatest Hit,” Dinosaur in a Haystack. ↩︎

- Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree”, American Literature, p. 470, footnote 2. The letter first saying the tale is from 1881 and is itself reporting hearsay from Wyatt, but there is no verification I am aware of that “W. W.”, the signature on the letter, knew Wyatt, that Wyatt told that story, or that Wyatt was telling the truth when he said it. ↩︎

- Warren, The Conchologist, 1834. ↩︎

- Isaac Lea, who may have been at least part of the force behind both Wyatt and Poe’s texts. ↩︎

- Wyatt, A Manual of Conchology, 1838, p. vi. ↩︎

- They retain an elevated status to this day. In the historical stories of zoology, paleontology, and evolutionary theory, the two central figures between Linneaus in the 18th century and Darwin (and Wallace) in 1859 are Lamarck and Cuvier. ↩︎

- Amy Robillard, “Pass It On: Revising the ‘Plagiarism is Theft’ Metaphor”, JAC 29, no. 1/2 (2009), p. 405-435, jstor.org/stable/20866995; cf. R. G. Martin, “Plagiarism and Originality: Some Remedies,” The English Journal 60, no. 5 (May 1971), p. 621-625, 628, jstor.org/stable/813078; Amy Vidali, “Embodying/Disabling Plagiarism”, JAC 31, no. 1/2 (2011), p. 248-266, jstor.org/stable/41709670. ↩︎

- Charles Rosen, “Influence: Plagiarism and Inspiration”, 19th Century Music 4, no. 2 (Autumn 1980), p. 88, jstor.org/stable/746707. ↩︎

- Vidali, “Embodying/Disabling Plagiarism”, JAC. ↩︎

- Letter from Poe to George Eveleth, February 16, 1847, The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, vol. 17. ↩︎

- Gould, in “Poe’s Greatest Hit,” believes Poe when he claims to have translated Cuvier, but no descriptions of Cuvier’s from his conchological/malacological entries appear to match those in Poe’s (or Wyatt’s) book. Gould, “Poe’s Greatest Hit,” Dinosaur in a Haystack, p. 182. ↩︎

- Charles F. Heartman and James R. Canny, A Bibliography of the First Printings of the Writings of Edgar Allan Poe, Together With A Record of First and Contemporary Later Printings of His Contributions to Annuals, Anthologies, Periodicals and Newspapers Issued During His Lifetime, Also Some Spurious Poeana and Fakes, Revised Edition, The Book Farm (Hattiesburg, Mississippi): 1943, p. 43. Accessed at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3910490. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Robillard, “Pass It On,” JAC. ↩︎

- Martin, “Plagiarism and Originality”, The English Journal. ↩︎

- For example, his descriptions of Dentalium (p. 12-13) and Scalaria (p. 129-130). Wyatt, A Manual of Conchology, 1838. ↩︎

- For example, Balanus (Poe, 1839, p. 31) is claimed to reside in “the Frith of Forth” (estuaries in Scotland) exclusively, when this is only true of the species Balanus candidus (Brown, 1833, p. 151). ↩︎

- Letter from Poe to George Eveleth, February 16, 1847, The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, vol. 17. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 278. Emphasis in original. “Pha” stands for Philadelphia. ↩︎

- That it was McMurtie and not Poe who published a book translating Cuvier makes this whole story just a bit more baffling. H. McMurtie, The Animal Kingdom, Arranged In Conformity with its Organization, by the Baron Cuvier: Translated From the French and Abridged for the Use of Schools, G. C. & H. Carvill (New York): 1832. Accessed at www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/108360. ↩︎

- Wyatt, A Synopsis of Natural History, 1839. As noted in Moldenhauer, “Beyond the Tamarind Tree”, American Literature, p. 472, Poe publicly claimed authorship of this book in 1845. ↩︎

- Edgar Allan Poe, “Review: A Synopsis of Natural History; Embracing the Natural History of Animals, with Human and General Animal Physiology, Botany, Vegetable Physiology, and Geology. Translated from the Latest French Edition of C. Lemmonnier, Professor of Natural History in the Royal College of Charlemagne; with Additions from the Works of Cuvier, Dumaril, Lacepede, etc. Arranged As a Text Book For Schools. By Thomas Wyatt, A. M., Author of Elements of Botany, A Manual of Conchology, etc. Thomas Wardle, Philadelphia.” Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1839. Compiled in The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Ed. James A. Harrison, Vol. 10, Crowell & Co. (New York): 1902, p. 26-27. ↩︎

- Letter from Poe to George Eveleth, February 16, 1847, The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, vol. 17, p. 278. ↩︎

- Robillard, “Pass It On,” JAC. ↩︎

- And then to also grade these assignments as practice in synthesis and transformation–a broken promise here would reinforce the necessity of plagiarism to the student a thousand times over. ↩︎

- Vidali, “Embodying/Disabling Plagiarism”, JAC. ↩︎